HR: Can you give us some context to this debate?

DW: In the 1950s, a student filed a lawsuit against the NCAA arguing his injuries should be covered based on an agency-employee relationship. The student won the claim, prompting the NCAA to develop the term “student athlete” to emphasize that players were students first and sports took a backseat priority. College sports are huge revenue drivers for the NCAA and universities. In light of the personal dedication and physical commitment required by sports, the issue is whether these players can be classified as students or if they are regular employees deserving of more compensation and benefits.

HR: So can you elaborate on what the current compensation model versus the “pay for play” alternative?

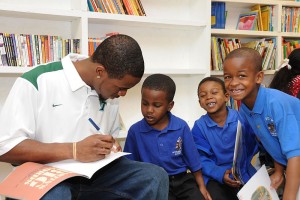

DW: The scholarship model is in place now which helps cover student expenses like university tuition, room, board, and books. While this alleviates some financial burden, the majority of student athletes still graduate from college with some form of debt. Additionally, some scholarships are so meager that they don’t reflect the true athlete’s value to the university they represent. I contrasted this model with a pay for play solution, which promises athletes a yearly salary according to their actual worth as players. Under this system, players are interpreted as employees for the school, enjoy better benefits, and postpone education attainment until after their contract.

HR: Are there benefits under the NCAA’s current system?

DW: Receiving a degree is the biggest advantage under the scholarship avenue. Popular literature has proven holding a degree translates into better future prospects and higher earnings. Because this mode is cheaper for schools, scholarships enables typically disadvantageous groups to participate in higher learning.

HR: What are the downsides under the current model?

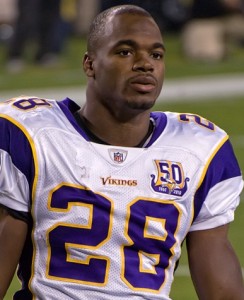

DW: The largest drawback is that athletes are not compensated at all for the commercial value they contribute to their school or the NCAA. For example, there was a lawsuit in September 2013 in which a UCLA student sued the NCAA and EA Sports for using his image in video games without proper compensation. There is added risk for permanent injury, which can ruin families financially and students professionally.

HR: So what’s the economics behind your study?

DW: I tried to forecast what a pay for play model would look like for football players and determine the implications for universities and the NCAA. I determined that under a pay for play model, college players should be compensated around $300,000 yearly for 5 years which is representative of the value they bring to their colleges and the NCAA. I anticipated the reactions to these increased costs is that universities would be more selective on recruiting, reduce player rosters, and earn less profits. Another consideration is how this change would impact the NFL draft. Right now, there is a surplus of college athletes that only a narrow percentage of them make it to the professional level. If universities were choosier in their players, it could illustrate to NFL which players are actually top talent.

HR: Is the pay for play model actually feasible?

DW: I decided that it ultimately wasn’t. It’s not only a tremendous cost to schools, but paying players would require a legal and administrational overhaul of their system. Right now, the idea is to slowly compensate the players more, so that all of their costs of schooling are covered.