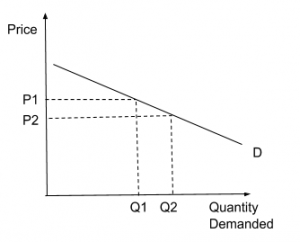

Subway’s five-dollar foot-long deal is no more. But when and why did this renowned campaign end? Simple economics can shed light into this decision: it was no longer profitable for Subway to continue to offer a sandwich for such a low price. In fact, in some locations it never was profitable, and many individual store owners have been contesting it since the beginning. Unlike many fast food chains in the United States, it is up to each Subway store owner to set the prices for their location that maximizes their individual profits. However, in 2004, Stuart Frankel had an idea in a Miami Subway store that offered a foot-long sub for $5 on the weekends. This trend quickly took off, and by 2008, the deal was launched all across the country, despite objections by a large portion of store owners. In the beginning, the deal was very profitable, there were not many other large chain sandwich shops, and as the law of demand shows us: as price decreases, the quantity demanded increases. Additionally, Subway faced an elastic demand curve, where a small change in price caused a large change in quantity consumed, as seen in the figure below. An increase in quantity demanded would bring in more customers into the shop, many of which would choose to purchase additional items such as chips or drinks.

But a lot has changed in the past ten years that have influenced Subways ability to keep up with these low prices. In order to determine optimal price and quantity to set in a perfectly competitive market for sandwiches, we will refer back to our condition to produce where marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. In this case, marginal revenue is equal to the price of the sandwich, indicating that it must be equal to the cost of making that sandwich (price of ingredients, paying the sandwich artists, etc.). Over the last ten years, a lot of these input prices have changed: labor costs have gone up, health standards have changed, and the marginal cost of making an additional sandwich is no longer less than the marginal revenue generated from the $5 deal.

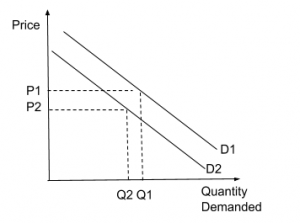

Subway also faced another issue: a decrease in demand for their sandwiches. As we learned in introductory economics, an increase in substitutes for a good affects the demand for the original good. As we saw a rise in other sandwich shops such as Jimmy Johns, Jersey Mikes, Panera, etc., many previously loyal Subway customers switched to alternative options. As the demand for the Subway sandwiches decreased (reflected in a downward shift in the demand curve), Subway was left with a lower quantity demanded, despite the low $5 price.

Now, Subway was producing less, charging less, but still incurred the same marginal cost for each sandwich. So what are we left with now? As of last September, it is no longer required for Subway stores to offer this deal to customers. Instead, it will be up to each individual store to decide if it is in their best interest to charge this low price. The decision will likely be made on the conditions mentioned above, including how the marginal revenue compares to the marginal cost of the sandwiches, as well as how competition in the area may affect the demand for their sandwiches.

http://time.com/money/5391437/subway-5-footlong-deal/

https://www.businessinsider.com/subway-backs-off-5-dollar-footlong-after-franchisee-revolt-2018-9