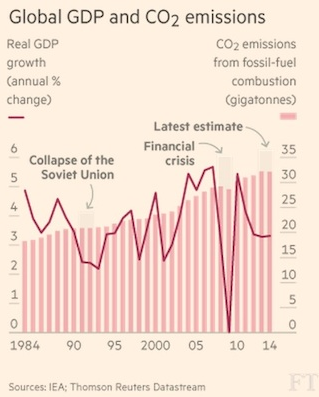

Two weeks ago, the International Energy Agency (IEA) reported that in 2014, there was a decoupling of economic growth and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. As the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew 3%, global emissions totaled to 32.3 billion tons, which was the same amount emitted in 2013. There were many reasons for this paramount shift, but to sum things up, many countries in different stages of development are finding considerable and effective methods in curbing their carbon emissions on both a household and industrial level. This is the first time in 40 years that a halt in global CO2 emissions wasn’t tied to a huge economic downturn. The only other instances that there wasn’t an increase in CO2 emissions was in the 1980s after the oil price shock, 1992 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and 2009 after the global financial crisis. Below is a graph of the level of GDP and carbon emissions:

Long ago, I promised myself that I wouldn’t use the term “game changer” in any of my blog posts, but I think it’s justified to make an exception in this instance. This information is a game changer for two reasons. First of all, if the trend continues, it will debunk the conventional wisdom that economic growth and carbon emissions must be closely and positively related. This newly broken tie between economic growth and increasing carbon emissions could change the way in which global leaders make policy decisions. IEA Chief Economist Fatih Birol stated that this information “provides much-needed momentum to negotiators preparing to forge a global climate change deal in Paris in December.” The upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference’s overarching goal is to review the actions each country outlined for the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions to limit the global temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Secondly, this is a game changer because it is beginning to show that national efforts to mitigate climate change are quantitatively having a more pronounced effect on emissions than what has previously been perceived by many lawmakers. The most prominent example is the actions of China. Its breakneck economic growth in the past couple decades has made it the biggest carbon emitter in the world, but they have recently been formulating ways to cut their emissions. Their main target has been decreasing their dependence on coal. By a long shot, coal is the dirtiest energy source due to the variety and quantity of polluting compounds it emits, and it makes up almost 2/3 of the country’s energy mix. This happened primarily due to the fact that historically, China’s effort to cut pollution had been secondary to the pursuit of accelerated industrial growth. Nevertheless, as health and social issues have started to devastate millions of citizens, this paradigm is shifting. In fact, Beijing plans to cut annual coal consumption by 13 million metric tons by 2017 from its 2012 level of 8.1 billion. One of the most robust actions to achieve this goal is that by 2016, Beijing will close the last of its four major coal-fired power plants and will be replaced by four gas-fired stations with the capacity to supply 2.6 more electricity than the old plants. These shut downs are estimated to reduce annual coal use by 9.2 metric tons and reduce carbon emissions by about 30 million tons.

Despite this decoupling in economic progress and higher carbon emissions, there is still much more work to be done. According to Don Wuebbles, an atmospheric science professor at University of Illinois, “The climate response that we’re seeing in the atmosphere now is largely due to emissions that happened 20 years ago.” This means that if emissions remain constant, concentrations of greenhouse gases will accumulate for even longer, leading to a continuation of the catastrophic effects that we are seeing today. Furthermore, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it would take about 100 years for the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to reduce to a third of its current levels. Fortunately, there will be opportunity to initiate progressive global environmental policy to limit future global warming at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference hosted in Paris from November 30th to December 11th.

So is this evidence for the “Environmental Kuznets Curve” (as the per capita income increases in a country the pollution levels drop)? This would be good news for other economies dealing with high levels of pollution (Mexico, Brazil, India) as income increases.