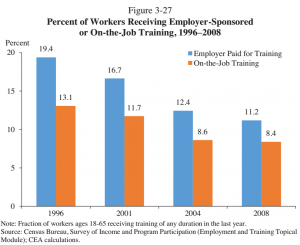

The Economic Report of the President was released recently, and in it was a sizable section on a trend of declining on-the-job training that identified a downward trend in it over the twelve years between 1996 and 2008. The last observation in the data was in 2008, but given the trends in the prior periods, there seems to be a distinct movement towards jobs with less on-site training.This is a concerning trend, however, when viewed from an efficiency standpoint.

In economics, economists identify two basic types of training. The first type is general training, and can be applied across a number of firms. An example of this would be basic mathematics. Knowing how to add two numbers together will likely make you a more productive employee, regardless of the firm you’re working for. You can go to an employer, and tell them “I can multiply two numbers together” and they will value your labor more than all of the other applicants who don’t know their multiplication tables. The other type of training is what’s called ‘specific training’ and really only applies for any given firm. An example of this type of training would be the knowledge of where the pencils are kept in an office. You could say to a potential future employer “I know where the pencils are kept at the last place I worked,” and while they’d likely be very happy for you, they also probably wouldn’t really factor it into their hiring decisions. (A link to Timothy Taylor’s explanation of this in relation to this data here.)

This distinction is quite important; it turns out, for our declining on-the-job training figures. When making decisions about providing training to employees, what firms really care about, as with everything else in economics, are the costs of providing that training, and the returns on that ‘investment.’ In this case, the returns on investment come from a worker completing labor that is more valuable than their wage until that training cost is recouped by the firm. So if that laborer can turn around and market their now-higher productivity in exchange for a higher wage, the employer will simply lose money by providing their employees with general training. Thus, specific training tends to make up the bulk of on-the-job training programs.

This factors into an efficiency problem because education and general training benefits not only the student or trainee, but also the firm they’ll likely go to work for. That is, education only offers a portion of its benefits to the student; who presumably pays some cost to gain this benefit. This leads to a below socially optimal level of training because the student/trainee will only value the training up to the point where the cost to receive that training is equal to the wage increase they expect to see. In addition, different individuals may face different costs to receive education, which will lead to an inefficient distribution of training across society.

The report implies that some of this discrepancy over time has been due to changing technological circumstances (or that jobs requiring specific training can be easily automated,) but it still represents something to watch in the next decade or so as middle-skilled jobs continue their decline.

Your blog posts are great, Connor. It’s a wonderful thing to learn economics from our students.