Whether it’s in my personal or academic life, I always have this desire to figure out why people do the things that they do. Fortunately, there’s a branch of economics for that. This past fall, I took a microeconomics class where we touched upon a topic that I found especially fascinating called Game Theory. In case you don’t know what it is, Game Theory is a strategy of analyzing decision making wherein a model is made to figure out the optimal strategies for two or more parties in some sort of competitive situation. Game Theory is used not just in economics, but also international relations, business, and even biology. Basically, it can be applied to almost any discipline that involves two people, parties, or organisms that have to make reactive decisions based on the actions of others. While writing a huge research paper on China-U.S. transboundary air pollution, I realized Game Theory can be applied to international negotiations on climate change, and more specifically, some historical decisions face the issue of the prisoner’s dilemma.

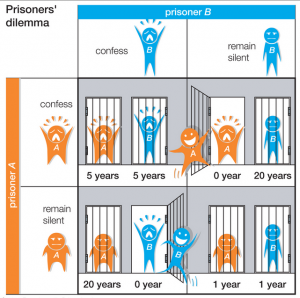

The prisoner’s dilemma is a concept in game theory in which two individuals acting in their own best interest take a course of action that doesn’t result in the pareto optimal outcome. Pareto optimality, also known as Pareto efficiency, is where resources are allocated in the most efficient manner where one party cannot improve their situation without making the other party worse off. The most cited example of the prisoner’s dilemma is that of two fellow robbers–let’s call them Bill and Ted– who are both suspected of robbing a bank and are being interrogated in separate rooms. Assuming that both of these men are rational, they want to minimize their jail sentence. Both men have the same option of either confessing against the other robber, or remaining silent. Based upon how both robbers plead, there are four outcomes of jail time. Below is a visual that is used in Game Theory that visualizes all of the options and helps conceptualize their decision-making:

As you can see, both Bill and Ted would spend the least amount of jail time if they both remained silent. On the other hand, it is in both robber’s best individual interest to confess the other’s guilt if the other remains silent. Due to the fact that they are unable to negotiate, both will rationally choose to confess, which leads to a non-socially optimal result.

This paradox can also be applied to climate change. Obviously, the socially optimal option is for all countries to reduce pollution. Unfortunately, the best individual outcome for any country would be for it to continue to pollute at the same, while other nations reduce their emissions. This is the case because pollution reduction requires structural and systematic changes that tend to be costly. Whether it involves switching energy dependence to a cleaner fuel, or producing less manufactured goods, most people go by the classic assumption that emitting less can stifle the economy (and up until recently, this was true). An absence of lower environmental regulations can also give countries a competitive advantage in production and trade compared to the countries that created regulations that work to limit emissions and reliance on fossil fuels. Because of this, countries theoretically tend to continue to pollute in the absence of any legitimate negotiation. Of course, this is an oversimplified explanation of global environmental politics game theory. The fact that international negotiations on climate change involve not two, but hundreds of parties, makes it complex beyond anything that I could attempt to explain. In addition, traditional game theory assumes that each party faces an identical payoff structure. Obviously, in the case of climate negotiations, this is not the case. Island nations such as Palau that face the risk of completely disappearing due to climate change-caused sea level rise have much more to gain from an improved international negotiation than a developed and already relatively environmentally sustainable country such as Germany. Nevertheless, the Prisoner’s Dilemma applied to global climate negotiations highlights the fact that on their own, countries won’t make the socially optimal decision, but rather, cooperation must happen.

Even when international agreements are established, Game Theory can explain why they don’t always work. Global climate change has only relatively recently been on the international political agenda beginning in 1992 when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) happened. Since then, there have been many other conventions with the best of intentions, but not very successful results. For example, the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement to set cuts to global greenhouse emissions in developed nations. The United States never ratified the treaty because it was stiffly opposed by Congress, who believed that it would harm their economy and their economic partners. Obviously, because the U.S. is such a huge voice in the international arena, how did the conference create a treaty that was destined to fail? A paper published in 2010 helps to explain the results with game theory. It explains when Al Gore and Bill Clinton came to the conference, they had already given up hope of achieving an agreement suitable for Senate’s approval. Nevertheless, they decided to negotiate an agreement that would “give the administration a friendly face” to other international politicians. Due to both asymmetric information and a poor understanding of the U.S. government system, negotiations led to an agreement that industrialized countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by an average of 5.2 percent by 2012 based on their 1990 levels. The countries in the conference assumed that because Gore and Clinton signed the treaty, it would be ratified. Obviously, this wasn’t the case, and the United State’s failure to sign the treaty was one of the multiple reasons why the Kyoto Protocol failed.

Game theory and the prisoner’s dilemma are both really insightful models for why transparent negotiation and cooperation is vital for most decisions. There usually tends to be winners and losers in global environmental politics, so decisions are rarely made in an efficient manner. As the adverse effects of climate change continue to become more imminent and countries grow more interconnected both in an economic and security sense, I’m sure that international climate change game theory will become an increasingly prominent topic.