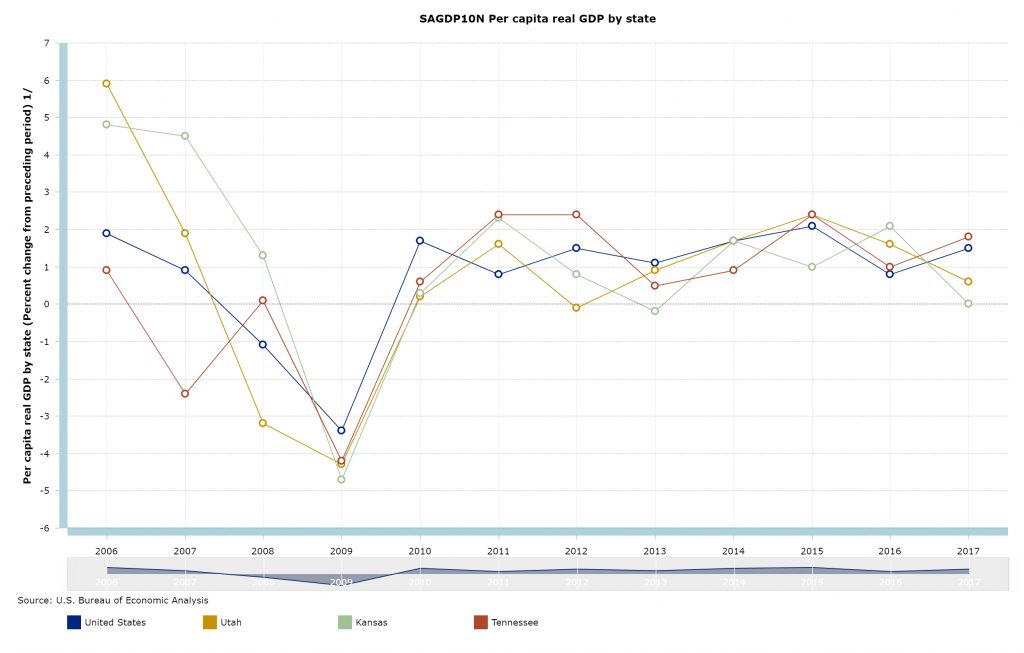

While it’s been 6 years since the Governor of Kansas, Sam Brownback, embarked on what is now known as the “Kansas Experiment”, its impact is still being felt by the economy and politics of Kansas today. Given the outcome, the real question is, was Kansas moving in a downward economic trend before the tax cut or was the tax cut the cause? The answer is: it was. I wish I could have drawn it out to a surprise conclusion or at least had some ambiguity to work with, but it is clear from the downgrading of the state credit rating (due to increased debt) and its relatively poor economic performance (see figure 1.) that the tax cut hurt a state that was otherwise doing decently. Currently if we compare Kansas to a similar state (population, landlocked, size, economy, etc.) such as Utah it becomes even more abundantly clear. In Utah there was 2.8% job growth (compared to 1.6% national average), a 0.5% net migration rate (compared to 0.3% national average), a $65,977 median household income (compared to a $58,552 national average), and a poverty rate of 10.2% (compared to a 14% national average). In Kansas on the other hand there was 0.3% job growth, a -0.3% net migration rate, a $54,935 median household income, and a 12.1% poverty rate. While this is not the worst of any state by a long-shot, a state that could have become one of the most economically viable mid-western states instead is relegated to the middle of the pack. Where did Kansas go wrong? It is easy to see the effects of the tax cut, but why did the tax cut have these effects? Many Neo-Keynesians and other such pro-government types may argue that government spending is more effective to drive growth, or that the tax cut only served to increase inequality or even that the tax cut would never have increased incomes enough to replace the lost tax revenue for the state government. While it is true that many of the these criticisms may be valid, I think it is important to look to a classic Keynesian assumption that tends to hold true: different income levels consume different amounts. When Brownback and the Kansas State legislature cut taxes, they mostly cut taxes for the highest earners by eliminating the highest tax bracket and by cutting the middle tax bracket from 3.1% to 2.7%. By cutting taxes for wealthier Kansas residents the government basically assured a lower return, as lower income individuals will consume more (spend more) compared with higher income individuals. Therefore, going back to the basic Keynesian principle, it would probably have made more sense to cut taxes for poorer Kansas residents and raised taxes for wealthier Kansas residents. Considering that the real per-capita income in Kansas is $30,146, cutting taxes at the lower end would most definitely have allowed many individuals in Kansas to spend on more than basic goods and services creating consumption growth. This is further supported by the fact that Kansas is a state that relies less on imports and exports compared with many similar states. Ultimately the sad fact is that not only is Kansas a decaying, unexceptional, lifeless, hinterland (economically speaking), but that it had the potential to be so much more.