As an economics student, few things make me happier than applying economics outside of the classroom. While I admittedly over do it (sorry Sara, Doug, and Jenna) I still love finding examples in everyday life. My favorite definition of economics is, “Economics is the social science concerned with how individuals, institutions, and society make choices under conditions of scarcity.” This is definitely different than most people’s idea of economics, which tends to be something like, “the branch of knowledge concerned with the production, consumption, and transfer of wealth.” In this article, I’m planning to briefly summarize many of the ideas I have had for posts here on the blog, but haven’t had time to develop fully. Some will fall into the more traditional idea of economics, whereas others may seem completely different.

I’ll try and sort these by where I think they fit, though many of them would undoubtedly take more research to clarify how they are embedded in the all-encompassing web that is economics.

“Traditional Economics”

—Boycotts

In the context of boycotting firms who produce with child labor, typically in the Global South, scholars have examined the effects of consumer boycotts in the form of social labels, which indicate and verify a project is made without child labor. For an example, t-shirts could be certified as made without child labor, and this would impact 4 groups of stakeholders: consumers in the producing (Southern) country and purchasing(Northern) country, Northern producers, Southern producers, and children in the Southern country. The study by Basu, Chau, and Grote (2006) found that in these situations, social labeling benefits consumers and Southern producers, but makes children and Northern producers worse off.

For the general consumer boycott, the evidence indicates that they are hard to accomplish in a meaningful way. While boycott announcements can reduce stock price (Pruitt & Friedman, 1986), they are difficult to enforce even for dedicated consumers who truly believe the boycott aligns with their values. This strays into behavioral economics, and difficulties in making intertemporal decisions.

—Food Labels and What Matters to Consumers: Organic, Local, etc

Since the Organic Foods Production Act established the National Organic Program (NOP) in 1990, consumers have been able to more easily identify crops and food produced via specific production practices. While consumers often don’t fully understand what specific labels mean, anecdotally and in the popular press, the idea is to support practices you ideologically support. In the research literature, many find that consumers who purchase organic products associate them with “small farms, animal welfare, deep sustainability, community support” though this has been disrupted as larger firms enter organic markets, leading to the idea of “organic lite” which seeks to profit off the ideas associated with organic (kind of a letter of the law versus the spirit of the law debate) (Adams & Salois, 2010). This may have driven consumers to seek out local foods, leading to a higher price commanded (Loureiro & Hine, 2002). Unfortunately, “local” is a fairly ill-defined term that could range from 1-500 miles.

—Economics of bankruptcy

After listening to a Planet Money podcast about bankruptcy, I looked into some of the concepts they covered. For example, US bankruptcy law, specifically Chapter 11, allow business to potentially recover from the inability to pay their debts, provided they follow guidelines laid out by a judge and their creditors. Some economists believe that our somewhat-unique bankruptcy structure is what enables the US economy to be so dynamic, because it provides a safety net for entrepreneurs to fail in their pursuit of success. (Jackson & Skeel, 2013). It also allows creditors to probably receive more of their money back than they would receive in a selling off of the bankrupt company’s assets. This isn’t to say that bankruptcy is all good, it can create perverse incentives in which workers and businesses take undue risks.

—Warranties as a Signal

A warranty is “a guarantee or promise which provides assurance by one party to the other party that specific facts or conditions are true or will happen.” When applied to products, a warranty generally either applies to the durability of the product (eg. cars) or the satisfaction of the customer (eg. REI products). For example, I recently purchased an Otterbox iPhone case, which offers a manufacturing warranty which usually results in them sending a new case if your case breaks (I’ve made use of this in the past).

Where warranties exert the most force in consumer decisions is in cases where the consumer is unfamiliar with the product, or the consumer is fairly risk averse. Then it acts as a signal, where a firm can credibly convey information through performing some costly action. Here, providing new products to consumers who either experienced defects or were unsatisfied is the costly action, which conveys that the company doesn’t expect that to happen often, otherwise it wouldn’t be an economically viable decision for them to make (and they might go bankrupt!)

Lastly, here’s a clip from one of my favorite movies, Tommy Boy, about guarantees.

“Non-traditional Economics”

—Using Laptops in Lecture: Opt-in, Opt-out, Laissez Faire

I don’t know about you, but there’s nothing more distracting to me than another student sitting in front of me browsing non-class-related materials on their laptop. If someone is online shopping for a new pair of Birkenstocks or browsing Imgur, I end up losing the thread of the class discussion. While I don’t understand the motivations of students who choose to mess around on their laptops during class, their choices impose a cost on my learning (in theory I could ignore it, but it never seems to work in practice). I also imagine that the time spent on activities unrelated to class must have an impact on a student’s performance in their course, however, some students are able to use laptops to enhance their learning. This leaves professors in an interesting position, should they choose to ban laptops and hurt those who could benefit? Or allow laptops and potentially let students distract themselves and others?

David Laibson, an economist at Harvard, has developed a new laptop policy for his students. For his Economics 1030 course, the laptop policy only allows electronic devices if students choose to opt into a laptop section. He is using this as a pilot study to examine the impacts of laptop use on students who self-select into the laptop using section, as compared to a non-laptop group. This intervention, as opposed to the standard laissez faire approach of letting students decide in the moment, taps into several ideas of behavioral economics.

One, people have a present bias, in which they tend to weight the benefits in the moment from the instant gratification of the Internet higher than the long-term benefits of getting a better grade.

Two, Laibson is tinkering with the choice architecture, or how the options are presented to students through framing and defaults. Behavioral economics has shown that people frequently take default options, so policy makers (or professors) should attempt to make the default the situation which will most likely benefit the decision maker. Many decision makers, especially college students, do not like choices being taken away from them, so a laptop ban may provide so much disutility that it reduces or eliminates potential positives from reduced distractions.

What Laibson ended up seeing was that students would often choose not to opt into the laptop section, because they were trying to commit themselves to better lecture practices. In an anonymous survey administered by Laibson and colleagues, students rated whether the laptop policy was bad (0) or good (10) for their ability to learn in the course. The average answer was 8.1, meaning that most students found it helpful.

—Economists and Marginal Decision Making

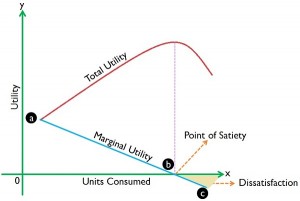

This one is more general, and really applies to any decision you can make. Assuming that decision makers are rational, an assumption which is often criticized, when making decisions, they would pick the option which results in a net marginal benefit, that is the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost of the decision. While total benefits are important, when making decisions which involve an additional unit, the marginal framework helps determine if you should make, buy, eat, drink, etc another.

For example, if I am out for beers at Engine House 9, I will consider the costs and benefits of each beer individually. Let’s say that I’m drinking an American lager, and it’s monetarily pretty cheap, and doesn’t have a very high alcohol content. This means that I will probably drink more lagers than if I was drinking IPAs which have a higher alcohol content and cost more. For both, let’s call the benefits the feeling of being intoxicated. At point B in the picture above, the benefit of an additional beer is less than the costs of an additional beer. I apologize for my inability to provide an exact number of beers at which I would reach point b, but maybe the Economics Department could sponsor a data collecting experiment? (I’m just kidding)

Another example could be studying. As I usually begin studying in the evening, I tend to stay up late to study. At some point, an additional hour of studying will have less benefits than costs in terms of lost sleep, and at that point I should stop. This is a little tricky as sometimes the costs of failing to complete an assignment makes me weight the sleep costs less heavily than the academic costs.

—Beauty versus a Beautiful Personality: Marginal Rate of Substitution

A brief disclaimer, this entirely intended as a thought experiment. I am not attempting to comment on the relative value of physical attractiveness as compared to the value of someone’s personality. I believe that in dating and marriage markets, potential partners should be evaluated holistically.

Culturally, there has been a construction of physically attractive people as having lackluster personalities, and less physically attractive people as possessing more positive character traits. While some research regarding the halo effect contradicts the idea that less handsome people will have a better personality, most would assume that pretty people are lacking in personality. An exchange from the movie When Harry Met Sally illustrates the pervasiveness of this concept.

Jess: So you’re saying she’s not that attractive.

Harry: No, I told you she is attractive.

Jess: Yeah but you also said she has a good personality.

Harry: She has a good personality.

[Jess stops walking, turns to Harry, raises his arms in the air]

Harry: What?

Jess: When someone’s not that attractive, they’re always described as having a good personality.

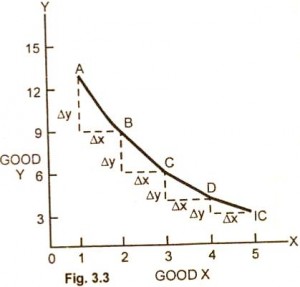

In microeconomics, economists examine how people maximize their utility, given budget constraints and their utility function. Oftentimes, they do this by creating indifference curves, which show different combinations of two goods that would generate the same level of utility. To calculate the level of utility generated by these combinations, economists use utility f unctions, which represent preferences over different goods, and mathematically express them. For example, a utility function for beer and doughnuts could look like this: u(b,d) = 2b + 1d, where the coefficient of 2 represents the higher value placed on beer. Basically, it would take 2 doughnuts to provide the same utility as one beer, or conversely 1/2 a beer is worth the same as 1 doughnut. The picture to the left shows a simple graphical representation of these ideas.

unctions, which represent preferences over different goods, and mathematically express them. For example, a utility function for beer and doughnuts could look like this: u(b,d) = 2b + 1d, where the coefficient of 2 represents the higher value placed on beer. Basically, it would take 2 doughnuts to provide the same utility as one beer, or conversely 1/2 a beer is worth the same as 1 doughnut. The picture to the left shows a simple graphical representation of these ideas.

We can apply this same reasoning to the trade-off between attractiveness and personality in potential mates, and could create a utility function for a specific person, and then subsequently find the rate at which this person is willing to trade beauty for personality, and vice versa. So let’s do an example. Let’s say there is a single, heterosexual woman named Jessica with the utility function: u(b,p) = 3b + 1p. Jessica ends up going on three dates over the course of a few weeks with men named Xavier, Yarrow, and Zachariah. According to Jessica’s subjective rating scales of 0-10 for beauty and personality, arranged (beauty, personality), Xavier scores (6,6), Yarrow (8,2), and Zachariah (5,9). If we compute the utility she would receive from each man, it comes out to uX=24, uY=26, uZ=24 meaning that the beautiful but boring Yarrow would be the rational choice. To put this in terms of marginal rate of substitution (MRS), Jessica’s MRS of beauty for personality is 3, meaning she would trade 3 personality for 1 beauty, or 1/3 of a beauty for 1 personality.