Let’s start this article off by saying, while I can’t say that scientists have proved climate change is real (nobody can really prove anything, even economists and scientists), I think the evidence is convincing enough that even if only 97% of scientists believe in anthropogenic climate change, we should probably still do something about it. 81% of climate economics experts believe that a market solution is critical, given that climate change has been called “the greatest market failure the world has seen,” by Nicholas Stern, an economist and climate researcher.

Essentially, there are three economic problems occurring with regard to climate change. One, a textbook negative externality, in which the people consuming/producing a good don’t pay for the damages experienced by a third party. Two, the costs of pollution are diffuse, whereas the benefits are concentrated, leading to difficulty in generating change. Lastly, there are difficulties associated with network effects, where the number of users impact the value of that good or service for others. For example, if you wanted to encourage electric vehicles, you’ll need a large, well-spaced network of charging stations or they’ll be inconvenient and ineffective for consumers.

In order to address these issues, many economists support a carbon tax. In order to tax carbon, we first need to price it. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used a measure called the social cost of carbon (SC-CO2)

The SC-CO2 is a measure, in dollars, of the long-term damage done by a ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in a given year. This dollar figure also represents the value of damages avoided for a small emission reduction (i.e., the benefit of a CO2 reduction).

The value of a ton of CO2 depends on the discount rate, which converts future economic value into present economic value or vice versa.

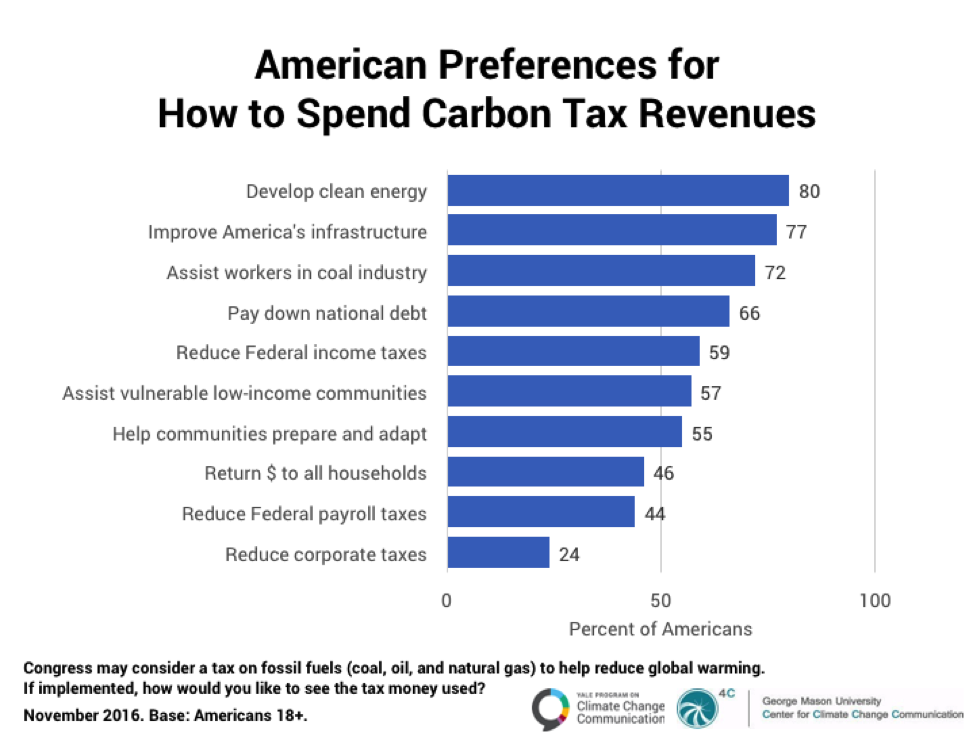

A new study by Kotchen,Turk, and Leiserowitz has found that on average, Americans would be willing to pay $177 in increased energy bills as a result of a carbon tax. The authors used the contingent valuation method, in which people are asked directly whether they would support or oppose a carbon tax which would cost their household x dollars more on their energy bill. An energy bill was used in order to create a more salient measure of cost per household, rather than an entirely theoretical cost. If this average increase was implemented, the tax would raise $22.3 billion a year in revenue. The survey also asked respondents how they would like revenue from the tax distributed, and the results are displayed below.

What it boils down to is this, 80% of their representative sample of Americans would like to see carbon tax revenue going towards clean energy. Furthermore, 72% would like to see the revenues going to assist workers in the coal industry, which would amount to roughly $146,000 per displaced worker in the coal industry.

This kind of survey is encouraging, but it really doesn’t address the problem. It does, however, show that this kind of carbon pricing is feasible. Now it is up to government and concerned citizens to make something like this happen, before it’s too late.