In which Daniel’s favorite author is the glorious sun, too bright to be near for too long, and he is the distant moon, only able to quietly reflect her brilliance at best.

To Ms. Valente,

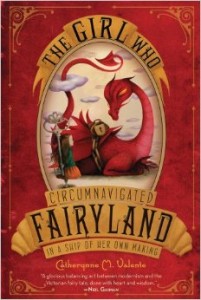

It is, in truth, to the University of Puget Sound that I owe my admiration for your work. I came upon the first book in your Fairyland series, The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, at the end of my first year of college while perusing the school’s bookstore. “What a delightful looking book,” I thought to myself (completely judging a book by its cover, as I am so prone to doing). “I think this would be a rather fitting reward to myself for surviving my first year at college.” Unable to resist, I bought the book and began to read it on my journey back to my home in North Carolina.

Immediately I was smitten. The difficult part is to say exactly why. The best explanation I can think of is this:

Have you ever been hungry for something and couldn’t say what it was? You wander around the kitchen of your house, opening the refrigerator and freezer and cupboards and drawers over and over again. Each time, you hope that your search will reveal what you’ve a hankering for, and each time, you are disappointed. But somehow, you continue along the way and happen to take a bite of something unexpected. Immediately, you realize that this is what your hunger has wanted all along.

Reading The Girl Who Circumnavigated for the first time was like that first bite. The love I’ve always had for both the possibilities of fiction and the nuances of language was suddenly reignited, and my mind came alive with new ideas and stories of my own. They say that you are what you eat, and swallowing up your words made in me something just as witty and sad and hilarious and timeless.

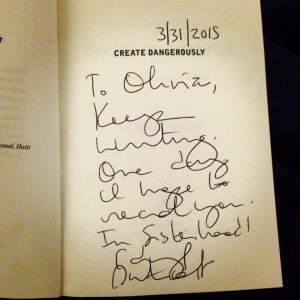

It was to my complete surprise when, over a 2 AM snack with a housemate, I was informed that you would be the closing keynote speaker at the science-fiction conference that the university was hosting – “The Once and Future Antiquity: Classical Traditions in Science Fiction and Fantasy” – on March 27th and 28th, 2015. The conference was to entail a series of lectures about how Ancient Roman and Greek culture have affected and shaped modern speculative fiction. I feel no shame in saying that I curled up on the kitchen floor in ecstasy. It’s fine. Let’s not discuss it.

The clever emblem of the University’s international “Once and Future Antiquity” Convention.

This joy was nothing compared to the actual act of watching you speak before me. It’s funny how someone you’ve always imagined can be both so much like and so much unlike what you’ve imagined them to be. You were just as funny, just as offhandedly charming and unconventionally inviting as I anticipated. You were much shorter than I thought you would be. Your voice was also much deeper. What you explained over the course of your keynote address, however, was something that I should have understood but had never considered: that you are so heavily influenced by classics.

Ms. Valente giving her keynote address to a packed audience in the Tahoma Room of the University of Puget Sound.

It is here that I am at a disadvantage. My knowledge of classics is limited to the point of being nonexistent. I am vaguely aware that the stories and myths of Greek and Roman civilization have been passed down through the generations of Western culture. I am vaguely aware that each time they have appeared, they have been transformed and reinterpreted, like a game of telephone. But I don’t know exactly what they are or what they meant to those cultures in their time.

During your keynote address, you explained many fascinating things. These included how you saw your childhood traveling between parents as a transformation of the Persephone myth, how your distinctive prose style initial arose from knowledge of multiple languages, and how your author superpower is that you are capable of writing remarkably quickly. What struck me most, however, is that when you were writing your first novel Labyrinth, you never considered it fiction because in the time of Ancient Greece, those myths were considered fact. Every story has mysterious labyrinths housing hungry minotaur, but it is mostly in fantasy fiction that these take their most obvious form. A minotaur might take the form of a librarian, or a principal, or a unpleasant waitress in other fiction, but the audience might not know that.

I doubt that you will ever read this.In some ways, I hope that you never do, so that the hour and a half I spent watching you lecture, meeting you and stealing the briefest of hugs from you will remain untarnished in my memory. In some ways, I hope that you will somehow stumble upon this, or that a friend will present it to you with a laugh, and that you will read it and be reminded of such a strange young man that did so love your children’s stories. Mostly, however, I just wanted to write this for my own sake.

Me attempting to maintain my composure beside Ms. Valente.

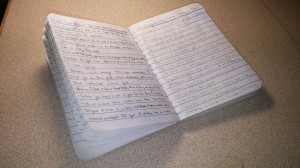

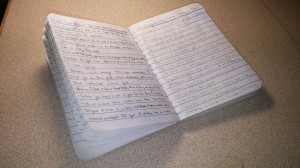

On one of the pages of my commonplace – a sort of intellectual logbook for quotable passages and facts – which I showed you, there is a page devoted solely to quotes from The Girl Who Circumnavigated. Each time I read the book, it never fails to entertain and touch me, but of all the wonderful passages I’ve copied down, the following is the one that struck me most, and to this day remains with me:

“As all mothers know, children travel faster than kisses. The speed of kisses is, in fact, what Doctor Fallow would call a cosmic constant. The speed of children has no limits.”

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert