In which we are faced with the curious knock of the wolf at the door.

To my dear reader,

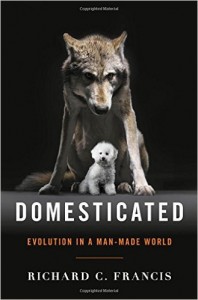

If you were to ask me about one thing in my life that I truly cared about, one of my first responses would be my pet Golden Retriever, Cinnamon Buns Flores Wolfert. Dogs are, America tells us, man’s best friend. But sometime last summer, I got to thinking about how curious of a view this is. It’s not one that has always existed, as there was once a time when dogs’ predecessors – wolves – were a force to be feared and reckoned with. It’s certainly not one that all people share – as dog cuisine in countries such as China make evident. This is not to criticize such countries, but rather to consider the question, why do I so love an animal whose ancestors tried to gobble up Little Red Riding Hood? It is to answer this question that, over this past summer, I read Richard Francis’ Domesticated: Evolution in a Man-Made World

*

Francis’ non-fictional exploration behind the biological, evolutionary and anthropological precedence of domestication is built primarily upon one premise: that domestication is the process of perpetuating tameness in a species. Tameness, Francis asserts, has been continually demonstrated in both studies and animal industry to be something that necessitates a genetic predisposition. Most wild animals are predisposed to fear and dislike heavy contact with one another and with humans, contrasting with the such domesticated creatures as attention-loving Golden Retrievers and tightly-quartered cows. Perpetuating tameness comes down to two, non-exclusive processes: commensalism and breeding. Both occurred on the journey from wolf and dog.

Commensalism – a relationship between individuals of two species in which one species obtains food or other benefits from the other without either harming or benefiting the latter – is often the first step of domestication. This was the origins of dogs when thousands of years ago, wolves stood as our most formidable competitors to be top of the food chain. Much like humans, wolves are social, hierarchical, and strategic. This pack-animal intelligence led to the more human-tolerant wolves to realize that they could scavenge humans’ scraps if they stayed near human settlements. Several generations later, the human-tolerant wolves survived more easily and passed along their tolerant genes, while the intolerant ones died more often and reproduced less.

Fast forward many more generations, and humans tentatively befriended the beasts that we once so feared. “If you can’t beat them”, said nature to the wolves, “join them,” and so they became our tentative hunting companions. It was not until humans began to breed them – to control wolf reproduction, allowing only the friendliest of wolves to mate – that true tameness became genetically ingrained. The perpetuation of human tolerance came with its own genetic package that can be found in almost every domesticated animal: one which includes things such as baby-like facial features, increased empathy, and quickened sexual maturity. This essentially meant the perpetuation of youthful characteristics into adulthood.

*

But how curious this all is! Let us take a moment to really, truly, consider the journey from wolf to dog. So many of the Western world’s fairy tales and legends include some sort of wolf as a villain. Little Red Riding Hood and her Grandmother get eaten by one, the Three Little Pigs’ property is invaded and damaged by one, and a professor of Hogwarts School of Witchcrft and Wizardry is cursed to become one at the full moon. Wolves are, so it seems, devious and terrible creatures intent on the worst. This is not to praise or criticize with this common Western view, but rather to contrast it with the view of dogs impressed on us now. Dogs are, so they say, intelligent beyond expectation and loyal to a fault. Dogs are, in a way, a testament to the power that humans have to shape nature.

Once more, this is not to praise or criticize the fact. It is rather that I find it so terribly curious how Cinnamon Buns Flores Wolfert and I are so happy to see one another, despite the fact that, were I to come home to a wolf, I would be terrified (and so might the wolf). I love her because long ago, my ancestors bred love into her ancestors’ very blood, and her ancestors were brought to their knees. All this, after all that time, when they said

Knock knock knock, let me in, let me in

and we said

Not by the hairs on my chinny-chin-chin.

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert