In which Daniel unravels Grandiloquence for Cello & Piano.

To my dear reader,

In another life, I am an English Major. My days are a torrent of essays and journals, my years marked by the tide of literary studies. I count the days down until the university’s annual fiction contest, and I know Wyatt – the university’s humanities building – better than my own house. Bits of stories and essays fill my backpack, and my room is an ocean of assigned readings that I can never quite seem to navigate.

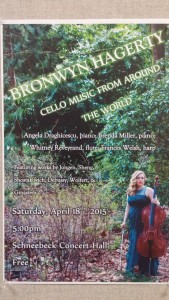

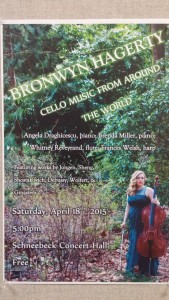

In this life, I am a music composition major, and that is perfectly wonderful. I do spend most of my days doing something I enjoy immensely, and I have learned so much about how to build a musical world in my past three years here. But in the recent weeks, a musical composition of mine entitled Grandiloquence for Cello & Piano was performed at cellist Bronwyn Hagerty’s senior recital (poster pictured below), and that piece rose from my unending fascination with words.

My name is beside Debussy’s. It’s not a big deal. Can we stop talking about it?

This love of grandiloquence – large words used for the purpose of sounding intelligent – is due to the children’s book series A Series of Unfortunate Events, by Lemony Snicket. The combination of misfortune, sardonic humor, ingenious orphans and dastardly mystery all tickled my fancy, but what really enthralled me as I read the series was the abundance of bombastic language. Words, as Mr. Snicket so elegantly demonstrated, are powerful, and being well-read can empower one in unimaginable ways as well as make one a better person. As the character of Justice Strauss said in The Penultimate Peril, “Wicked people never have time for reading. It’s one of the reasons for their wickedness”.

Lemony Snicket, who may or may not be the pen name of author Daniel Handler, pictured above.

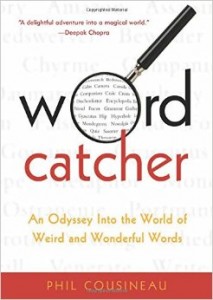

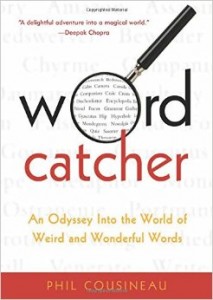

Grandiloquence itself, however, is a product of my fascination with another book, by American author and filmmaker Phil Cousineau, entitled Wordcatcher: An Odyssey into the Weird and Wonderful World of Words. I read this book only once a few years ago, but the way that the book explored the history and etymology of the world’s most distinctive words has long since remained with me. Particularly unique words, such as noctambulation – the act of wandering about the streets at night – or spoffle – meaning to trifle about with trivial matters for the sake of looking important or busy – sparked stories in my mind, and alongside those stories came characters and music.

My subsequent desire to express the music I heard in these words manifested itself in a project I would call Grandiloquence for Cello & Piano. Written expressly for Duo Con Fuoco – a pair comprising Puget Sound cello performance major Bronwyn Hagerty, ’15, and Puget Sound piano performance and biology double major Brenda Miller, ’15 – each movement of the piece is titled with a different bombastic word and musically illustrates that word’s definition.

Bronwyn Hagerty, left, myself, center, Brenda Miller, right.

The three movements that I have composed thus far for the project are the following:

https://soundcloud.com/dwolfert/sets/grandiloquence-for-cello-piano

I. Twee – (adj.) excessively sweet and adorable to the point of being repulsive: Making use of the baroque counterpoint of Bach and Haydn, this movement opens with the presentation of an annoyingly dainty melodic idea in the cello. The piano then proceeds to present the same in melodic idea in a completely different key, and the two instruments battle to see which can be more disgustingly cute. Feel free to tell me which you think won.

II. Rapacious – (adj.) exceedingly greedy and grasping in nature: After an opening of atonal notes in the cello over a piano drone, a gentle lullaby melody rises from the piano, drifting back and forth between it and the cello. As the music progresses, however, atonality begins to slither back into the piano accompaniment, and by the movement’s ending, the cello melody has been completely gobbled up by the insatiable piano.

III. Espérance – (Middle French, n.) the hope that feeds the soul: With an opening motivic piano figure that echoes the opening of Sondheim’s musical Sunday in the Park with George, this third and final movement is a kaleidoscope of old church modes, trills and virtuosic melody. After a series of piano flourishes, the cello spins out a sweet and simple melody over clear piano chords that builds before leading into a new melody supported by tumbling piano arpeggiations. The piece spins and whirls over the cascade of notes before fading back to the sweet and simple piano chords of the opening – but with the cello whirling back in at the last moment to provide an expectant but unresolved ending. This is all meant to show both the inspiring beauty and the restless, inexorable momentum of hope.

I have no regrets about choosing a major in music over a major in English. To me, the language of words and the language of music are somehow two halves of the same whole. Composing this piece was the result of seeing how I could bring those two halves together, and I believe that this is the reason that this is the composition of mine that I am thus far most proud of. Enjoy!

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert