In which Daniel considers the mentors of basketball coach John Wooden, as well as his own.

To my dear reader,

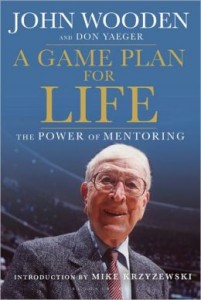

I have always had an aversion to sports. There are many reasons for this, among them my small physical stature, my lack of bodily coordination, my distrust of the concept of “teamwork,” and the negative dissonance between social constructions of athleticism and homosexuality. But despite all of these reasons, a figure that has begun to loom large over my life is that of John Wooden, now late basketball coach, literature teacher, and author.

Alongside his remarkable achievements in the field of athletics, including leading the UCLA Bruins to ten championships in his time as coach, Wooden has become incredibly well known as a fountain of wisdom on the subjects of teamwork, discipline and life over all. It is only after reading his book A Game Plan for Life: The Power of Mentoring have I truly realized how much he has been an “invisible mentor” – a teacher that I have never met but has continually guided me through his writings and teachings – and all in spite of my initial trepidation.

This got me thinking about the role of mentors within my life, and who they have been thus far. In his writing, Wooden made a point of saying that mentors need not be people that one has necessarily met, but I believe that this principle extends farther: mentors need not even be real people. I have certainly felt more mentored by many fictional people than by the real people in my life, and the effects of this are no less valid or real. Thus came to be the following list of the seven most prominent mentors of my life:

1. Katy Perry

“If stars don’t align, if it doesn’t stop time, if you can’t see the sign, wait for it.”

I first truly came in contact with Katy Perry’s music during the end of my senior year of high school. I had decided, on a whim, to put her Teenage Dream album on my iPod, and sharing this album with Spencer Orbegozo – a classmate that was destined to become my best friend – was, unwittingly, one of the best decisions of my life. This album became the cornerstone of our friendship, and came to me at a time when I needed something that would propel my into the future. The simple, optimistic beauty of the line “Let’s run away, and don’t ever look back” encapsulates all the joyful momentum that I do not possess, but wish to have. Alongside opening me up to the world of trashy pop (an inexhaustible source of joy for me), Katy Perry taught me to look to the future with hope.

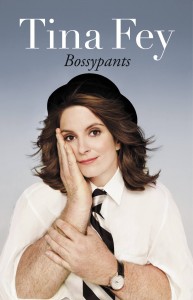

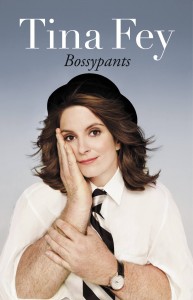

2.Tina Fey

“To say I’m an overrated troll, when you have never even seen me guard a bridge, is patently unfair.”

If there is one mentor on this list that I am most similar to, it is undoubtedly Tina Fey. In her genius autobiography Bossypants, Miss Fey cites strong parental influence, bad skin, and love of musical theater as the driving forces of her life – if that doesn’t describe my life, what does? But more than simply providing me with a famous face to identify with, Tina Fey (and Bossypants itself) demonstrated the ability to laugh at one’s failures and find humor in the endless drudgery of life. Tina Fey taught me to accept my own disastrous self.

3. Uncle Iroh

“Destiny is a funny thing. You never know how things are going to work out. But if you keep an open mind and an open heart, I promise you will find your own destiny someday.”

Being the most fictional of my mentors, it is somewhat more difficult to explain how this character from the TV show Avatar: The Last Airbender has affected me. Avatar was only one of many fascinations I held as a child, the others including the works of Lemony Snicket and the Harry Potter series, yet no character in those other stories held as much sway over me as Iroh. Across the TV series, Iroh acts as the protective uncle and gentle guide to the series’ troubled antihero (his nephew), providing comic relief and wise perspective in equal measure. But it was the humanity of Iroh that really struck me. Iroh became angry at his nephew when his nephew was too prideful, became weary from his turbulent life, and became hungry more or less constantly. Iroh taught me not only to love tea, but also life, with good humor and perspective.

4. Tarn Wilson

“Write the book you would want to read.”

When I first joined her creative writing class in my junior year of high school, Tarn Wilson was merely another very nice and intelligent teacher employed by Gunn High School. After I turned in an autobiographical work describing some serious emotional troubles, however, Ms. Wilson called me into her office and had me speak with her to ensure I was emotionally healthy. Tarn Wilson taught me many suprising and insightful things about writing itself, but taught me even more about the act of creation – creating a story and creating a life. Life will not appear, she explained, until you do – not your parents or teachers or friends or even mentors, but you. Tarn Wilson taught me that my life is a story, and I must learn to be its author.

5. Cathrynne M. Valente

“As all mothers know, children travel faster than kisses. The speed of kisses is, in fact, what Doctor Fallow would call a cosmic constant. The speed of children has no limits.”

I recently wrote a blog post detailing my feelings toward science fiction and fantasy author Cathrynne M. Valente, which can be found here (http://blogs.pugetsound.edu/whatwedo/2015/04/01/an-open-letter-to-catherynne-m-valente/), but to get to the heart of what I mean to say, it is crucial to understand my first experience with her writing. I first discovered her book The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making the summer after my freshman year of college, and just like Teenage Dream, this book came to me at a time when I very much needed magic in my life. Over and over again in her literary works, Miss Valente has demonstrated a delicate mastery of intelligence, whimsy, humor and sensitivity that I can only dream of one day achieving. Cathrynne M. Valente taught me to find magic in all facets of life.

6. John Wooden

“Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.”

By far the most pragmatic of my mentors, basketball coach John Wooden was introduced to me through my fraternity’s leadership program, the Wooden Institute. What struck me most about Wooden when I learned of him was his dedication to organization. Something that Wooden is famous for is his process of teaching new players the proper way to put on socks. He would ensure that the socks fit on snugly and without wrinkles, and that the laces were pulled and tied firmly, so as to avoid loose shoes, and therefore, blisters. This would ensure greater comfort during practice, leading to more better practice technique and ultimately better training. Many, if not all, of Wooden’s accomplishments demonstrate his commitment to quality, but this simple and tangible action demonstrated this to me the most. John Wooden taught me dedication to performing effective work.

7. Spencer Orbegozo

“There truly is no me without you.”

Of all my mentors, the one with the most powerful, immediate, lasting and obvious impact on me is my best friend. After spending a year in freshman Physical Education together during high school, we overcame our initial dislike for one another. This tentative peace became a tentative friendship, which eventually became the bond that remains to this day. Spencer and I call one another every other weekend, and periodically write letters of extreme length and detail to one another. He has taught me more things than I can count, and more than I’m sure I could actually recall, but more than anything, Spencer has taught me to believe in the worth of oneself no matter how others think. Spencer taught me, in the words of Gladys Knight and the Pips (a band he is fond of), to “keep on keepin’ on.”

And that’s just what I’ll do.

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert