I didn’t know a lot about modern Irish history when I came over here. I taught myself about the Easter Rising because I loved Yeats and I knew he loved a woman who was involved in it, but it was so much bigger than I could have understood on my own. I’ve been learning about it for seven weeks now and it’s terrifying. I had to write my first midterm paper on my perspective on the Northern Irish Troubles. After visiting Belfast over midterm break, I have images that convey something of what has gone on in that city. I’m in no way an expert, but I don’t think a lot of people know about the conflict in Ireland that’s still going on. Here’s a quick history lesson, taken almost verbatim from the paper I turned in yesterday. Yes, there’s a bibliography at the end of this for anyone who’s curious. You can also Wiki any of these events. Or you can skip this history lesson and ignore Irish troubles. A lot of America does.

The animosity the exists between Catholics and Protestants can be traced back to the plantations of Ulster which began to appear in 1609. Protestant farmers took Catholic land in an attempt to introduce ‘civilized’ British living to the ‘wilds’ of Ireland. This led to the Catholic slaughter of Protestants in 1641; Cromwell’s suppression of Catholics in 1652; and, eventually, the Williamite-Jacobite War that took place between 1698 and 1691. The partitioning of Ireland supported Protestant control, as Unionists insisted that Northern Ireland should only consist of the six most Protestant counties of the nine counties of Ulster, ensuring that Protestants would hold the majority in elections. This strategy succeeded; throughout the political history of Northern Ireland, Unionist members of Parliament consistently outnumbered Republicans until Britain disbanded the Northern Irish Parliament of Stormont in 1972 after Bloody Sunday.

A student currently living in Northern Ireland spoke of the fear of Catholic violence which is still promoted and impressed upon Protestant children today. Catholics still feel like they’re oppressed. Since the formation of the Northern Irish state in 1921, Catholic citizens suffered under Protestant Unionist social reforms such as the Special Powers Act. These reforms resulted in severe oppression, including Catholic unemployment rates that, in the 1970s and 80s, were three times higher than Protestant unemployment rates.

The Catholics borrowed tactics from the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and began peaceful protests for their own civil rights. When the protests were ignored by politicians or attacked by Unionist-affiliated policemen and civilians, this led to violent outbursts such as the Battle of the Bogside and the creation of Free Derry. While Catholics previously sought change by working within the political system, when Bogside homes were threatened by police forces, the Catholics went for weapons rather than political reforms. This created a self-sustaining loop, for Protestant fears of Catholic rebellion were realized when Catholic Republicans rose up against them; Protestant Unionists still refused to yield to Republican demands for civil rights, and thus Catholics fought back all the harder.

Britain itself had little interest in Northern Irish affairs and is still seeking to find a way for Northern Ireland to govern itself with little to no British involvement. This would only be possible, however, through a collaboration among Catholics and Protestants. Both Unionists and Republicans must be invested in the state’s well-being before Northern Ireland can be politically stable without British intervention. With Protestants still seeking to control Northern Irish politics, though, and with the rise of Catholic political parties who work within the parliamentary system to bring it down, it is unlikely that such a collaboration will take place soon. At least, that’s what I think after two months of learning about this. I could be wrong.

Anyway, this is what I knew going into our Northern Ireland trip.

When we arrived in Belfast after a three hour train ride, we had to pay with British sterling instead of euros. The signs were only in English, no Irish to be seen anywhere. They call their Bulmers cider Magners even though it’s the same label, same taste. It was very…strange.

Also, Belfast is a very new city. It’s been bombed and rebuilt so many times, I don’t think there were buildings over fifty years old there.

We went to see the Belfast murals. The first ones we saw were in Shankill, a Protestant neighborhood.

This one says “Nothing about us without us is for us.” The government has been trying to get rid of the Belfast murals for quite a while now but the people who live in the neighborhoods with this art are resisting. The mural is made up of pictures of people who live in this neighborhood.

The reason the government dislikes the murals is most likely because some of them

are pretty terrifying. This one’s showing how scary the IRA is. The IRA is the Irish Republican Army over here. They plant bombs. Two were defused while we were in Belfast, we learned later.

Some murals have a history lesson behind them.

This is the Red Hand of Ulster. Two chieftains were bookin it towards land because who ever touched the land first would own it. The losing chieftain cut off his own hand and threw it so it landed first and thus he won Ulster. Hooray! Never surrender! Northern Ireland is made up of six of the nine counties of Ulster, so they use this symbol on their flags.

Then we went out of Shankill…

This is the checkpoint people pass through to get from Protestant Shankill to the Catholic Falls area of Belfast. It’s open until around 6 at night. It closes completely on weekends. It’s a part of one of the longest Peace Walls that runs through Belfast.

This peace wall runs all the way up onto that hill you can see in the distance. It’s seriously huge. Belfast asked graffiti artists from around the world to come and make it prettier (as pretty as a 60-foot-high wall made of concrete, corrugated metal, and chain link fencing can be). Even cooler is the fact that the men who drive the Black Cabs in the Black Cab Tours dole out pens and crayons so visitors can add their own marks to the wall.

There were a lot of messages promoting reconciliation, understanding, and compromise. There were messages of solidarity, love, and tolerance. There was a surprisingly small amount of filthy graffiti up there. I’m kind of proud of people.

Anyway, we made it into the Falls.

They had a whole row of murals that commemorated their own struggles, but also expressed their solidarity with other causes. There was a copy of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica and a couple other political uprisings that the Catholics apparently condone.

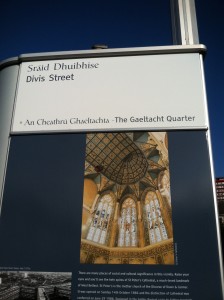

This was also the only place I saw Gaelic in Belfast!

By the way, I really doubt that this was a Gaetacht. They totes spoke English more than they spoke Irish. That’s fine, though, at least they learned Irish at all. Irish makes me kind of happy, in case you can’t tell.

So, these are some of the things I saw in Belfast. I got some very interesting perspectives on the Troubles from the Black Cab drivers, saw some disturbing images, got hassled by twelve year olds, and saw no violence even though it turns out some almost happened while we were there. A successful Belfast trip!

(Here’s my bibliography for the interested:

Dixon, Paul. Northern Ireland: The Politics of War and Peace. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

Farrell, Michael. Northern Ireland: The Orange State. London: Pluto, 1980.

Feeney, Brian. Sinn Féin: A Hundred Turbulent Years. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 2003.

Moloney, Ed. A Secret History of the IRA. London: Penguin, 2003.)