The best part about working in the Archives & Special Collections? Stumbling across something you did not expect to find.

The best part about working in the Archives & Special Collections? Stumbling across something you did not expect to find.

This past year, Maya Steinborn ’14, Zeb Howell ’16, and Morgan Ford ’17, have chronicled the materials they found interesting and exciting while working in the Archives & Special Collections. A BIG thank you to each of them for their contributions!

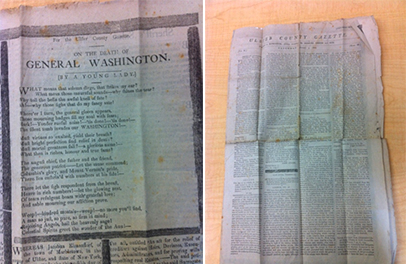

Most often an archival collection arrives at our door in complete disarray, a pile of boxes with folders, objects, books, and even some Q-tips thrown in. There is no order and little identification. We go through these boxes making sense of the madness so that researchers might spend less time digging through boxes and more time studying the material that is actually relevant to their research. In the past six years I have come across quite a few unexpected discoveries while digging through boxes: copious amounts of hair, a sombrero, a powder horn, letters signed by U.S. Presidents and Civil War generals, and most recently an issue of the Ulster County Gazette, January 4, 1800.

This item emerged from the papers of Walter S. Davis (1866-1943), a professor of history and political science from 1907-1943. I was quite excited to find this issue; it is the first paper to report the death of George Washington! Then I began to do some research, it turns out this issue of the Ulster County Gazette was widely reproduced as a historical souvenir. In fact, only two originals are known to exist, one at the Library of Congress and the other at the American Antiquarian Society.

Stop by the Archives & Special Collections to see this exciting reproduction of the Ulster County Gazette and learn how to distinguish the originals from the fakes!