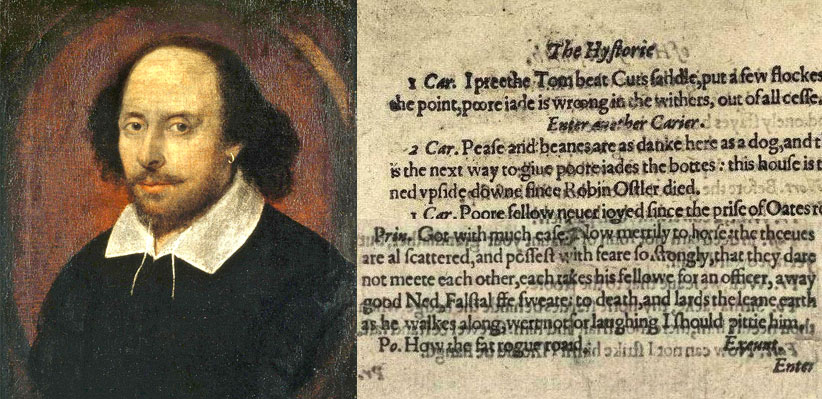

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

Congratulations to our wonderful first-year writers. For additional online resources about Shakespeare, check out these sites:

- British Library: http://www.bl.uk/

- Folger Shakespeare Library: http://www.folger.edu/

- Globe Theatre: http://www.shakespearesglobe.com

- Internet Shakespeare Editions: http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca

- Shakespeare 400: http://www.shakespeare400.org/

Broken Windows

By Bobbi Ford

I don’t know about you, but growing up I read one of Shakespeare’s plays every year, and every year it was intimidating. When I was younger the language was hard to comprehend, now that I’m older the concepts are what stumbles me. It seems that there has always been a certain ambiguity that comes along with Shakespeare. We try extensively to understand and theorize who William Shakespeare was personally – not just one of, if not the greatest playwright of all time. Analyzing his sonnets and plays to not only learn the bigger picture he was trying to create but rather what that vision can tell us about him politically, socially, or even romantically. If we take into account his works, the books he may have had access to, the political movements of that time, and who he got to work with, we can create a more realistic picture of how each piece of his life effected his plays. More specifically, if we look into the religious background of England we gain a bigger understanding of Shakespeare and his plays as a whole.

It is hard to say for certain anything about Shakespeare’s personal life, especially something as private as what religion he practiced. However, we do know that Protestantism became the official religion of England the year before Shakespeare was born in 1563 (Goaby). With that, we can infer that he was aware of its ceremonies and other attributes including its reformation of catholic churches through whitewashing. This was done essentially to remove “distractions”, such as intricate stained-glass windows and paintings of saints covering the walls in the church to let the word of god be the focal point. One in particular, the “right goodly chapel” in Stratford-upon-Avon – where Shakespeare was from – had a glazier come to town to shatter the beautiful stained-glass windows and replacing them with clear glass. Since this was a public event chances are he was there as a child watching it unfold. (Shapiro) Seeing this could have effected how Shakespeare perceived religion and furthermore influenced his writings.

In Shakespeare’s time many things were changing and a change in religion added another confusing factor. Many official Catholic holidays that had been celebrated for years were no longer celebrated and new protestant holidays were added to the mix. This disrupted their everyday life because there was a certain way to dress for holidays, usually a special hat. When you don’t know what is a holiday and what isn’t there can be a lot of confusion. This problem bleeds into some of his plays including Love’s Labor’s Lost and Julius Caesar (Shapiro). In the opening scene of Julius Caesar, a common man and a cobbler are dressed for the holiday, two men, Flavius and Murellius confront them for wearing holiday attire on a workday, however, it was actually a holiday (Julius Caesar 1.1). This confusion directly parallels with how the Elizabethans were always questioning “Is This a Holiday?” like in James Shapiro’s book, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, 1599 explains.

Another larger problem was time for the Elizabethans and was only worsened by the divide in religion. People were off of the calendar by about ten days. To fix this a pope suggested to skip day to get back on track. This seemed like reasonable and easy solution until the Protestant countries didn’t agree, consequently Easter was celebrated five weeks apart (Shapiro). In Julius Caesar, the very noble and smart Brutus asked what the date is which if you didn’t understand the problem with time back then you would be very confused why such an intellectual man would ask such a silly question (Shakespeare, Julius Caesar 1.2). Things like this and many others seemed to have directed influenced his plays. Though we can’t know for sure much about Shakespeare we can use the historical events surrounding him to help better understand his plays and even further, why his historical plays are so important in understanding him.

Bibliography

Goadby, Edwin. “Protestantism in Elizabethan England.” Shakespeare’s Religion. Shakespeare Online, 2011. Web. 28 Feb. 2016.

William, Page. Portrait of Shakespeare. 1884. Photograph. Folger, Shakespeare Library. folger.edu. Web. 28 Feb 2016

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar. Broadview Press: Internet Shakespeare Editions. 2012. Print.

Shapiro, James. “Is This a Holiday?” A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, 1599. Harper Collins Publishers. 2005. Print.