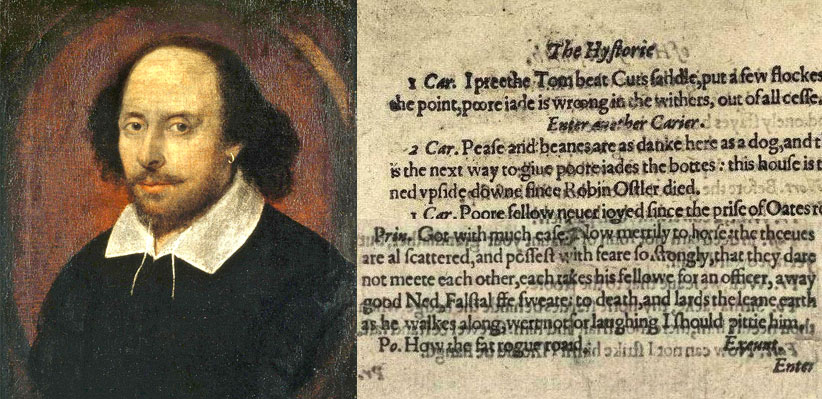

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

Congratulations to our wonderful first-year writers. For additional online resources about Shakespeare, check out these sites:

- British Library: http://www.bl.uk/

- Folger Shakespeare Library: http://www.folger.edu/

- Globe Theatre: http://www.shakespearesglobe.com

- Internet Shakespeare Editions: http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca

- Shakespeare 400: http://www.shakespeare400.org/

Shakespeare in Plague-Ridden London

By Lindsey Rachel Hunt

William Shakespeare died 400 years ago, in April of 2016. But, thanks to the plague’s many sweeps through London, he could have actually died much, much sooner. While the plague hit London particularly hard in 1665, it actually struck the city fairly hard in 1592-93, 1603, and 1606 (British Medical Journal). The plague was explained with a variety of unusual causes; sinning, foul or sick air, the alignment of the planets, and imbalances of the four humors that were believed at the time to control the physical health and emotional well-being of humans (British Medical Journal). Symptoms of the plague included a high fever, severe joint pain, thirst, delirium, heart failure, and the swelling and then rupturing of lymphs located in the groin, neck, and armpits (Shapiro).

Despite the plague’s high contagiousness and terrifying symptoms, life in Elizabethan England went on. Whenever the plague would ramp up the death count, privy councilors in charge of maintaining quarantines would complain that “too many Londoners were washing off the red crosses painted over the doors of their infected and quarantined households.” (Shapiro) Londoners were also much more likely to break rules and London descended into chaos during bouts of plague; law enforcement had to sit tight, and magistrates and (ironically enough) physicians left the city (British Medical Journal). After 1603 experienced an “outbreak in which more than 30,000 Londoners had died, the privy council decreed that public playing should cease once the number of those who died every week of plague rose ‘above the number of 30’.” (Shapiro) Players frequently disregarded this decree, choosing instead to keep their theaters open even when the death count was nearing 40. When the death toll was as high as it got to in 1603 or 1606, however, the playhouses remained closed. Some historians actually claim that “there is a close correlation between the closure of the playhouses and Shakespeare’s writing habits,” arguing that Shakespeare practically ceased writing altogether whenever the plague took more victims (Shakespeare Quarterly). The idea that outside circumstances heavily influenced Shakespeare’s creative output is not a foreign concept; in the SSI-2 class A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, we frequently compare real-world events in the year 1599 to the plays Shakespeare produced during that time period.

While we will never really fully know why Shakespeare chose not to write plays during theater closures, we do know that Shakespeare lived in a part of the city that, for the majority of the outbreaks, remained relatively safe from the plague. Shakespeare lived in the parish of St. Olave’s of Silver Street, which, in the plague-ridden years of 1592, 1593, and 1603, remained relatively unaffected by the rest of the city’s illness and panic. It wasn’t until 1606 that plague seemed to have struck Shakespeare’s community. There’s even a chance that Shakespeare’s landlady was affected, although the vicar, Flint, “listed only the date and the deceased’s name and occupation…Flint sometimes included a stray detail, [but] his entries are brief,” so she could have died from other causes (Shapiro). Even so, the plague was too close to Shakespeare for comfort.

If the plague had touched Shakespeare in 1606, some of his most notable plays, like Winter’s Tale (1610) and The Tempest (1611), would never have existed. In a lecture Dr. Wesley gave during my Orientation the previous semester, I learned that Shakespeare was educated primarily with morality plays. Morality plays had simple characters that represented moral concepts that needed to be reinforced. These morality plays were commonly shown in theaters along with a variety of simple, silly plays; as a result, theater wasn’t taken seriously. An exceptionally hard worker like Shakespeare was needed to change the purpose of going to the theater from simple entertainment to a provocative learning experience. While another playwright could have emerged and taken Shakespeare’s place in the annuls of history, I’m glad Shakespeare survived to write his sonnets and plays. Since you’re reading this, I’m sure you are too.

Bibliography

“The Plague in Shakespeare’s London”. “The Plague in Shakespeare’s London”. The British Medical Journal 1.3187 (1922): 156–156. Web…

Book reviews – politics, plague, and shakespeare’s theater: (1993). Shakespeare Quarterly, 44(1), 100. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.ups.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1811840?accountid=1627

Shapiro, James. How Shakespeare’s great escape from the plague changed theatre The Guardian.com, 24 September, 2015. Web. Accessed 1 March, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/sep/24/shakespeares-great-escape-plague-1606–james-shapiro