In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

Congratulations to our wonderful first-year writers. For additional online resources about Shakespeare, check out these sites:

- British Library: http://www.bl.uk/

- Folger Shakespeare Library: http://www.folger.edu/

- Globe Theatre: http://www.shakespearesglobe.com

- Internet Shakespeare Editions: http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca

- Shakespeare 400: http://www.shakespeare400.org/

No Legacy is so Rich as Honesty

By Aidan Regan

During the summer of 2014, I undertook an apprenticeship through the Idaho Shakespeare Festival, a ten-week long hurly-burly of perspiration and perseverance. It included, among other things, the memorization, working, re-working, re-re-working, and performance of a real Shakespearean monologue—and not just any monologue, but one opposite to what we’d normally be cast. I, typically very composed, was allotted a murderous tirade of Caliban’s from The Tempest, who’s both drunk for the first time and half-fish. I could envisage a crystal clear image of Caliban and how he should be played, but no matter what I tried, something was missing from my performance; some element of Caliban’s truth was lost on me—that is, until taking one of the apprenticeship’s master classes taught by a phenomenal actor named M.A.

M.A. had each of us apprentices perform our monologue for him (in the midst of its “re-re-working stage”) and midway through gave us a directorial twist: to do it AS A PIRATE. I shut one of my eyes, made a hook gesture with my hand, and elongated my R’s. Afterrrrrrwards he asked us all why we’d made those specific decisions, to which we had no answers. They were simply performative impulses made on the spur of the moment. But instead of critiquing our decisions, he dropped a mantra with a singularly profound impact on us all: “Pirates don’t apologize.” It taught me that while I couldn’t make my performance of Caliban perfect, I could make it mine. Likewise, any decision I make, whither in my acting or in my life, is the right one as long as I’m honest with myself and own it.

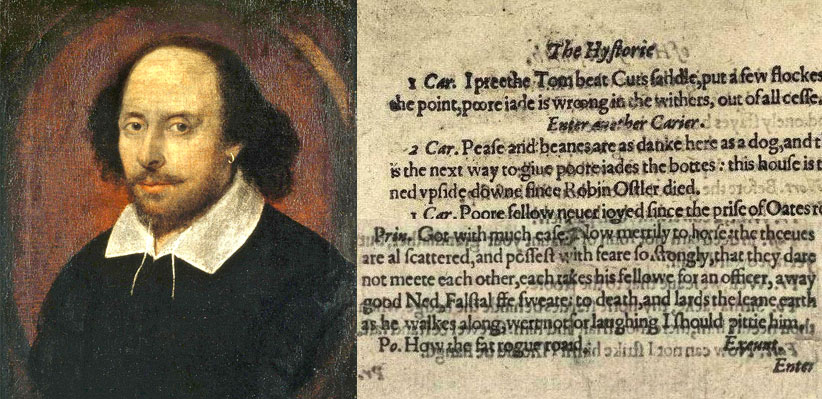

This lesson applies equally to the performance of any one of the characters in Shakespeare’s plays. By embracing their own individual take on the role, actors can make their performance more real, more honest, and entirely new to the stage; as Mariana says in All’s Well That Ends Well, “No legacy is so rich as honesty” (3.5.14). Shakespeare’s plays have had such legacy and appeal over the past 400 years simply because every one of his characters lends themselves to the versatility of an individual’s interpretation. This fact has been recognized by several Shakespeare scholars, including Simon Palfrey, who writes in Doing Shakespeare that “The recognition that they [characters] are prescripted or bounded by dramatic materials leads to a search for that which lies within or beyond such materials; similarly, the absence of explanation or evidence makes us try to supply both. The characters we locate are our constructions, without substance outside our experience of them…in that they are hardly less real than any other thing we call our own” (322). All actors need to do for their performance to work and their rendition to be real is to follow in the footsteps of Will Kemp, Shakespeare’s clown who’s pictured above, and dance to the beat of their own drum.

Bibliography

Kempes Nine Daies Wonder. 31 Dec. 1599. Illustration. Wikimedia Commons.

Palfrey, Simon. Doing Shakespeare. N.p.: Bloomsbury, 2014. Print.

Shakespeare, William. Complete Works. Vol. 7. New York: Hearst’s International, 1909. Print.