In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

Congratulations to our wonderful first-year writers. For additional online resources about Shakespeare, check out these sites:

Hamlet’s Development

By Leah Ikenberry

Hamlet is one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies in the classical sense. The character of Hamlet is a very complex character and undergoes a huge amount of psychological development over the course of the play in a very short time. One question that is commonly asked is about Hamlet’s age and while he may have a set physical age the age he represents developmentally throughout the play changes. A brief overview of this theory shows Hamlet’s age anywhere from seven to thirty-five.

At the play’s beginning, Hamlet is dealing with his father’s funeral. He shows a wide variety of emotions. He is questioning everything through his emotions which represents the developmental age of fourteen. Emotions are overwhelming and experienced to the fullest and emotional limits are tested. “In this latter [Hamlet] case the initial effect is strengthened by contrast: against the foil of extreme hypocrisy of Claudius and of the flatters who pander to him, the profound sincerity of Hamlet is overwhelming… a man dedicated to truth and allergic to falsity in any form, a soul that reverberates with love of good and abhorrence of evil” (Lings 27). When Hamlet encounters his father’s ghost in Act I Scene V where he learns the truth of his father’s death. “The serpent that did sting thy father’s life/ Now wears his crown” (38-39). This information endows him with responsibilities and the development of the ego and sense of self confidence usually associated with the age of twenty-one.

At age twenty-eight a person tends to question what they are doing with their life or make a change in career. Hamlet reaches this point when he sets up his uncle during Act III Scene II in “The Mouse-trap” which is a play that acts out the murder of Hamlet’s father by Claudius’ hand (224). Hamlet confirms Claudius’ guilt with Horatio.

Hamlet: “O good Horatio, I’ll take the ghost’s word for a thousand pound. Didst

perceive?”

Horatio: “Very well, my lord.”

Hamlet: “Upon the talk of the pois’ning?”

Horatio: “I did very well note him” (271-5).

Now Hamlet has to decide what to do with this information and this forces Hamlet to make a conscious life shift which occurs around the developmental age of thirty-five and is Hamlet’s physical age according to the Gravedigger or First Clown in Act V Scene I “Why, here in Denmark. I have sexton here, man and boy, of thirty years” (151-2). It was already established Hamlet was five when the sexton came. Hamlet conscious does not kill Claudius while he is praying at the alter “Now I do it pat, now ’a is a-praying; / And now I’ll do’t – and so ‘a goes to heaven, / And so am I reveng’d. That woud be scann’d: / I, his sole son, do this same villain send/ To heaven” (3.3.73-8). From this point on Hamlet is consciously making his own decisions instead of swayed by other influences.

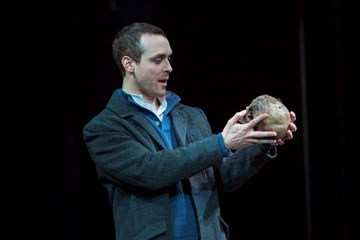

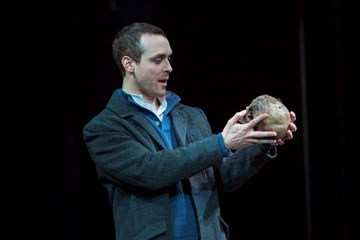

The figure of Hamlet holding the skull of Yorick from a production of Hamlet performed at the Denver Center Theater Company. http://extras.mnginteractive.com/live/media/site36/2014/0212/20140212__20140214_C1_AE14THREVIEW~p1.jpg

During one of the most famous speeches in Hamlet, the titular character relives the developmental age of seven. This speech is found in Act V Scene I and Hamlet relives his childhood while addressing the skull of Yorick. “Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio, a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He hath bore me on his back a thousand times, and now how abhorr’d in my imagination it is!” (172-5). Seven is the age of the imagination and seeing the possibilities in the universe, Hamlet remembers this as well as his possibilities now.

The end of Hamlet, Hamlet is at peace within himself and no longer has a fear of death. He welcomes death as a person usually associated with the age of forty-two. He dies in the arms of Horatio. “Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince, / And flights of angles sing thee to thy rest!” (5.2.341-3).

This theory of how one man can experience the different stages of life within a short amount of time is very revealing. It also shows how physical age is only a number and does not directly relate to how that person is exploring the world developmentally. Each and every person may experience all of these stages according to the associated age while others may never reach any of these stages. It depends on the person and how they relate to the universe and themselves.

Bibliography

Lings, Martin. Shakespeare’s Window into the Soul: The Mystical Wisdom in Shakespeare’s Characters. United States: Inner Traditions, 2006. Print

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Boston, MA: Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 1994. Print.

The figure of Hamlet holding the skull of Yorick from a production of Hamlet performed at the Denver Center Theater Company. Taken from the Denver Center.

http://extras.mnginteractive.com/live/media/site36/2014/0212/20140212__20140214_C1_AE14THREVIEW~p1.jpg