In which Daniel teaches you to speak a little Dinosaur.

To my dear reader,

In the last week of classes of the Fall 2014 semester, I decided that, since my choir class had been canceled for the day, I would sit in on the student presentations in the music history class “Music in the Twentieth Century”. This class, intended for non-music majors, was a sort of little brother of the music major history class I was taking, “Music Since 1914”, and I was curious about the presentations of the friends I knew taking the class. I was also curious, however, about the views that on-music majors held on the place, significance and purpose of music. Amid the mass of desks, the fifteen student presenters each paired with one non-presenter and sat down to give their one-on-one presentation, changing partners every ten minutes.

The prompt of the presentation was to answer the question “What is good music?” (in the light of all they’d learned about music perspectives and recent history), and I was mightily impressed by the first two presenters. The first, who was a good friend of mine, gave an eloquent presentation on why the Beatles demonstrated good music by means of pushing boundaries while communicating effectively with their audience. The second, who I had not met before, gave a concise but effective presentation on how electronic music, by means of recognizing and utilizing past music to create music of the future, exemplified good music through innovation. The third presenter, however, gave me pause.

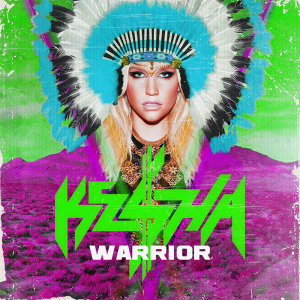

The premise of his argument was that true music serves some sort of purpose, and that there are three categories of music. The first is music that simply fulfills its function, giving the example of Ke$ha, whose music seemed to him solely for the purpose of dancing. The second is music that fulfills its function and creates a feeling in the listener, giving the example of a rock song I hadn’t heard of, which for him brought back nostalgic memories. The third is music that fulfills its function, creates a feeling in its listener, and makes the listener think, giving the example fo a rap song I hadn’t heard which compelled him to sympathize with the poor and consider their plight. Given my boundless love for Ke$ha, I suppose we got off on the wrong foot from the get-go. Yet considering my feelings for Ke$ha and his argument together as objectively as I could, I couldn’t help but find his argument unconvincing. Let me explain:

Category One: Yes, Ke$ha’s music serves its economic purpose of being dance music. This music is sold with the intent of being primarily danced to, and so it is written, arranged, produced and recorded with the intention of creating a consumer good that consumers will desire and subsequently consume. People want dance music, Ke$ha and her collaborators create it, people buy it. Effective indeed.

Category Two: While for this presenter, Ke$ha’s music was cold plastic, my experiences with Ke$ha’s music made me feel differently. I associate Ke$ha primarily with my best friend, with whom I spend an enormous amount of time bonding over self-indulgent pop music. What with the positive associations I have with my best friend, the number of times we’ve had Ke$ha dance parties in my friend’s car, the letters we’ve written to one another quoting Ke$ha, and the general hilarity of the self-empowerment that Ke$ha bestows, I cannot help but smile when I hear her. This is not to say that everyone (or really anyone else) will feel the hope and power and joy that I feel listening to Ke$ha, but rather that feelings are subjective.

Category Three: Being cold plastic to the presenter, Ke$ha’s music is intended to make people dance and to be sold to consumers, with no intellectualism being part of the final product. But what makes him think and what makes me think are different. What with the associations with my best friend, listening to Ke$ha makes me think of that friend and all the complexities of our relationship. Moreover, Ke$ha makes me consider the complexities and injustice of gender roles. By this, I mean that when people think of Ke$ha, they think “slut”, in the sort of tone implying shame and insult. Why? Because society says that a woman displaying sexuality is inappropriate and shameful, while a man – such as Pitbull – displaying sexuality with such lyrics as “face down, booty up, that’s the way we like to what” (from the song “Timber”, coincidentally featuring Ke$ha) is acceptable. Disregarding the social boundaries impressed upon her as a woman, Ke$ha still wants you to “pull over and spread ‘em, let {her} see what you’re packing inside of that denim” (from the song “Gold Trans Am”). She does not ask permission for being a human being with sexuality.

Ultimately, the fault I saw with this argument was that what makes one person think and feel is completely different from what makes another person think and feel. With something as subjective as music, almost all aspects of preference are enculturated, meaning that what’s happened in our lives and who we are around leads us to prefer some things over others. Nothing in music is good or bad. It simply is, and maybe you like it or maybe you don’t. Many cultures use mictrotunings that, to American ears, sound like instruments are broken, but that doesn’t mean it’s bad. It’s just different from what American ears know. But don’t take my word for it – let this interview with Ke$ha convince you:

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert