As I wrap up the Library as Collaboratory course and reflect on what I learned, I am amazed at the stark contrast from what I expected when I signed up for this course. All it took for me to add this course to my shopping cart was that the quarter credit that fit into my schedule and most importantly it was about libraries in someway. When I found out that the course was actually about digital humanities and how the liberal arts could be used in a work setting, I was all the more ecstatic. As a college senior I was looking for any and all opportunities on how I could use my degree, and in this age of rapid fire technological growth, becoming competent in anything digital seemed to be a win win.

The course was set up so that each person in the class would be working in small groups with a librarian on a project that incorporated the digital humanities. We would be in charge of project design, managing our own timeline, and communicating with the other group members and the librarian to get the project done. By a grab-bag choice, I worked on the zine metadata project. I knew almost nothing about metadata and only cursory information about zines, so I was guaranteed to learn something from this project.

Metadata is what makes the four stories of our library searchable with the single click of a button. According to Merriam-Webster, metadata has the titillating definition of ‘data that describes other data.’ For the library, this means any information they have logged about a specific item, such as a book or a magazine, in the collection. This is all searchable data, and it is what pops up when you are looking for a specific item in the library using a computer.

I have worked with metadata for many years now; it was a key part of how I found resources for references for my countless research papers and, well, anything in the library. However, I had never put any thought at all into how those small paragraphs under book titles with my searched phrases highlighted in yellow popped up. I might have thought at one point that they were pulled from the abstracts of books, or that some combination of publisher, author, and librarian compiled the list, or even that they were computer generated (I’m not sure how this would have worked, but that’s kind of the point, isn’t it?).

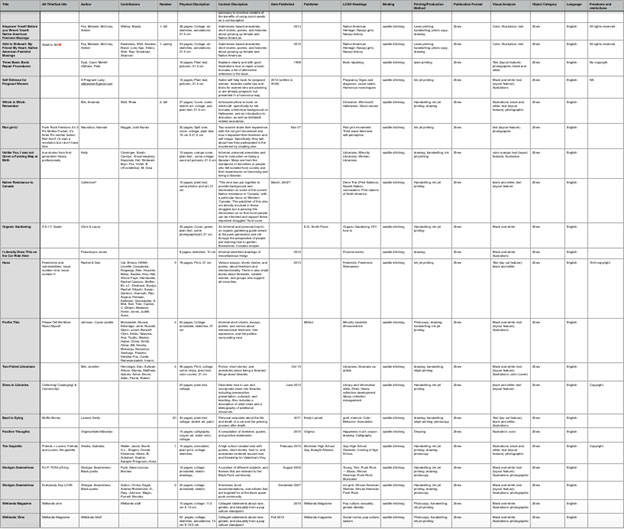

When I was tasked with creating metadata for the zines, I thought that I would just be summarizing the content and listing important data such as title and author. This is what I actually ended up doing:

Creating metadata is actually a very specific process; for many of the columns you see I had to use controlled vocabulary, which meant that I could only use words from a list. For example, under ‘binding’ I couldn’t just put ‘stapled,’ I had to put ‘saddle stitching.’ This may all seem entirely too bureaucratic and finicky to be of any actual use, but this is all for a purpose. Remember; all of this information is going to be searchable soon. It needs to make sense, and because metadata is created by many different people all the time, there needs to be some standards for what is put in when and where to make sure utter chaos does not reign.

Of course, the format of a zine doesn’t always lend itself to easy metadata. Zine as a genre continually defy defining. The only requirements for a zine being categorized as such is that it needs to have a small publication, and they are generally the size of a regular sheet of printer paper folded in quarters. However, even these loose definitions can be and are bent, and mostly if a creator claims that what they published is a zine, then that is what it is. There are no regulations to include a copyright nor the name of the author. Often a single zine can cover many different genres and topic within the span of only a dozen or so pages.

As maddening as that all was, though, it was also an integral part to what makes zines so important. They are often written by people or groups of people who feel outcast or marginalized by society. They are the results of people struggling to make themselves heard on a platform which they control and which can’t be controlled by anyone else. These little pamphlets hold some of the most raw and honest accounts of what it is like to be human that I’ve ever read, and it has been an honor to read them.

By Ada Smith