I would like to open this blog post with a quote from my friend from this week’s archival research, Dr. Henry Brown:

“Indeed our common Christianity is in jeopardy from the universal prevalence and insidious attacks of the forces of evil resident in, and emanating from, the popular amusements of the day”

– From the preface of his book, Impending Peril, Or, Methodism and Amusements

After spending the first half of my week with Dr. Brown, I have found Brown to be a surprising character with deeply held, but sometimes seemingly contradictory beliefs.

Brown lived from 1848-1931, and thus experienced some very interesting periods of American history. Our collection of his papers includes the autobiography that he dictated to his wife as he was nearing the end of his life, which details some of his more important life experiences. Only a teenager during the civil war, Brown fought for the Union, and turned 16 on a battlefield. He was a deeply religious and moralistic man, and became a minister as a young adult after the Civil War ended. He first preached in Iowa, but after 14 years, in 1885, Brown was transferred to Ellensburg, Washington. Brown, his wife and their two small daughters traveled across the country by train. Brown spent the bulk of his career in Eastern Washington, staying in Ellensburg a year before moving to Walla Walla and eventually to Spokane.

In addition to his autobiography, the collection includes two albums in which Brown collected newspaper clippings. A quick perusal of the clippings reveals Brown’s near constant back and forth with the editors of the Walla Walla Daily Journal, and The Oregonian throughout the 1890s. Brown was a staunch prohibitionist, a sentiment that the editors of the two newspapers did not seem to share. Brown would write a scathing letter to the editor critiquing their representation of prohibition and its supporters, and the editor would write an equally impolite response, which would in turn prompt yet another letter to the editor from Brown. At one point, The Union Newspaper goes so far as to title his letter to the editor as, “Brown the Irrepressible.”

Brown was also a passionate supporter of women’s suffrage, and wrote many a letter to the editor about the way that women’s newly legal right in Washington territory (which was one of the first territories to grant voting rights to women) was represented in the Walla Walla Daily Journal, which stated that “The Union does not believe in forcing the women of the territory to vote.” In response, Brown pointed out that men were not “forced” to vote either and that in saying that the Union did not believe in forcing women to vote, the Journal was really saying that, “the Union does believe in forcing the women to refrain from voting. In other words, the Union would strengthen and perpetuate the manmade legal barricade that now stands between women and the polls.” Brown also took issue with the claim made by the paper that women had only voted in the first election merely for the novelty and curiosity of it, but had since refrained from voting, writing that he, “would be glad to know the names of some of those intelligent women who had no higher notion in casting their first ballot than simply to gratify their curiosity.”

Brown’s vocal support of his causes did not end with letters to the editor, however. In 1904, Brown published his first and only book, The Impending Peril, or, Methodism and Amusements: A Compilation of Testimony, Rules, Speeches, and Articles on the Amusement Question with an Argument in Review, which describes the dangers that popular past times pose to Christianity- going to the theater, to concerts, to dance halls, or to the race course, and of course the consumption of alcoholic beverages at any of these amusements were all deemed unacceptable past times for Methodists.

Brown eventually retired and spent the remainder of his life in Pomona, Ca, where he was still an active member of the Methodist church, and where, I’m sure, he wrote at least a few letters to the editors of the local papers.

Brown has thoroughly entertained me for the past few days- while he has at times confused me by his seemingly contradictory beliefs which don’t quite fit so neatly into the stereotype of his peers from the same era, I have found that his deeply held convictions come from his very strong belief in morality. A man who didn’t believe in war, Brown fought for the Union in the Civil War because he felt it to be a just cause. Brown was a vocal supporter of both prohibition and women’s suffrage (two pretty unpopular causes during his day) because he believed in the innate rightness of these two issues. And even though I find some of his arguments problematic, to say the least, particularly concerning prohibition and those in his book on the evil of popular amusements, I have to admire the guy for his commitment to his beliefs.

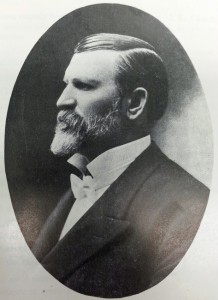

And he does have a pretty great beard, so there’s that too. By

By: Kara E. Flynn