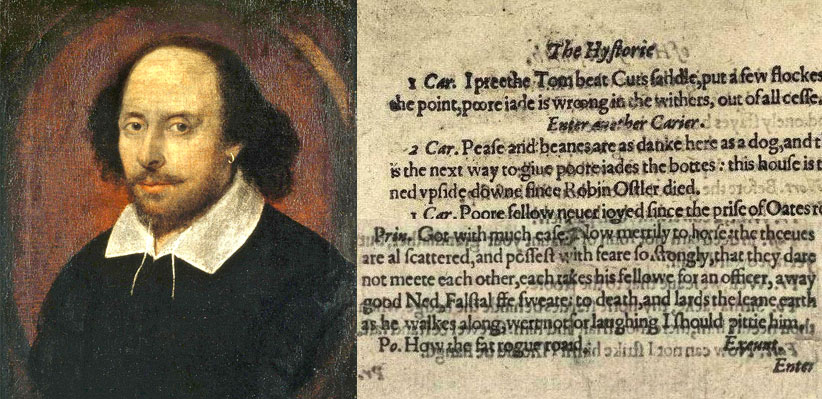

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

In honor of William Shakespeare we are celebrating the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23, 2016. What better way to do this, than by highlighting the writing done by first-year students in Associate Professor of English John Wesley’s first-year seminar, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare? This first-year seminar in scholarly inquiry studies four remarkable plays Shakespeare wrote or saw into production in 1599, the same year he opened the Globe Theatre. In the first half of the course, students were introduced to the myriad ways in which Shakespeare’s 1599 plays are shaped by and give shape to the political and cultural intrigues of that year. In the second half of the course, students turned to a play (and year) of their own choosing, the historicist analysis of which is the basis of an independent research project. As part of this project, students were asked to prepare a blog post that reflected on aspects of Shakespeare’s life, a specific work, or a resource or organization associated with Shakespeare, or to provide a personal interpretation of a play. During the month of April, we’ll feature the posts from students that celebrate all things Shakespeare!

Congratulations to our wonderful first-year writers. For additional online resources about Shakespeare, check out these sites:

- British Library: http://www.bl.uk/

- Folger Shakespeare Library: http://www.folger.edu/

- Globe Theatre: http://www.shakespearesglobe.com

- Internet Shakespeare Editions: http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca

- Shakespeare 400: http://www.shakespeare400.org/

Shakespeare’s Words

By Cory Koehler

When confronted with Shakespearean writing, some people enjoy the challenge and his stories, others grimace and try to work their way through the muddle, and still others flat out refuse to make the attempt. The archaic language and phrasing mixed with iambic pentameter and references that are no longer common knowledge can easily lead to distress and confusion. But in some respects, those of us reading Shakespeare’s plays in the modern age have an advantage over his original audiences. Beyond the benefit of having the internet at our disposal, we also are already familiar with many neologisms of Shakespeare’s that they may never have come across before. Currently, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) accredits Shakespeare with coining 1,507 words, and creating 7,698 new definitions for existing words. Some are common words that we take for granted, such as downstairs, ghost, list, purr, and defeated. Others are obscure words that hardly anyone knows, like facinorous– meaning extremely wicked or immoral– and scamel– a word so seldom used that even the OED doesn’t know the meaning (Oxford).

When confronted with Shakespearean writing, some people enjoy the challenge and his stories, others grimace and try to work their way through the muddle, and still others flat out refuse to make the attempt. The archaic language and phrasing mixed with iambic pentameter and references that are no longer common knowledge can easily lead to distress and confusion. But in some respects, those of us reading Shakespeare’s plays in the modern age have an advantage over his original audiences. Beyond the benefit of having the internet at our disposal, we also are already familiar with many neologisms of Shakespeare’s that they may never have come across before. Currently, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) accredits Shakespeare with coining 1,507 words, and creating 7,698 new definitions for existing words. Some are common words that we take for granted, such as downstairs, ghost, list, purr, and defeated. Others are obscure words that hardly anyone knows, like facinorous– meaning extremely wicked or immoral– and scamel– a word so seldom used that even the OED doesn’t know the meaning (Oxford).

Unfortunately, it cannot be completely confirmed that Shakespeare himself created these words, only that his are the oldest recorded instances of their use. He could have heard some of those words from plays that didn’t survive or in passing from a person on the street. Some of his supposed neologisms have been found in older works as have been since stricken from his tally. Despite his reputation as a wordsmith and the impressive count of words still accredited to him, Shakespeare is not the author with the most neologisms. That distinction goes to Geoffrey Chaucer followed closely by John Trevisa, who are the only two individuals whose new-word counts exceed Shakespeare’s. While he doesn’t hold the record for new words, Shakespeare does have the most new definitions for existing words and is the single most quoted author in the OED with tallies at 7,698 and 33,076. Only The Times has more quotations or new meanings with 40,406 and 7,757, respectively, and they have had innumerable authors and two and a half centuries to amass that collection and they are still creating more (Oxford).

In spite of plethora of words in the English language, new words are continually being created. Some neologisms are needed for new inventions and the descriptive words that go along with its behavior or use, such as Twitter, hashtag, and tweet, although two of those are existing words that have been given new meaning. Others are coined for no particular purpose, but by word of mouth and the indomitable influence of the internet. There are also a few nonce terms that are created for a single occasion, one that don’t survive their coinage or are only applicable in an author’s writing, such as terminology for that specific fictional world. Words like flowgold, zan, and concraz (three words from my current favorite book: Earth Girl by Janet Edwards) don’t hold much meaning beyond the pages of their book. For anyone wishing to dabble in coining neologisms, there are already existing terms for creating words that might help you along: combining and shortening, using prefixes, suffixes, and syllables to do just as the words imply; blending, adding two words together; borrowing, taking words from other languages; and Eponymic naming, turning proper nouns into other parts of speech (Plotnik). Or you could simply create a new word from scratch, as many sci-fi and fantasy authors do. However you choose to neologize, don’t be afraid to share it with others. Who knows? It could become the next word added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Bibliography

Plotnik, Arthur. “Shall we coin a term? When no other word will do, maybe a neologism will.” The Writer Dec. 2003: 17+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 28 Feb. 2016.

“William Shakespeare.” Top 1000 Sources in the OED. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016. Oxford English Dictionary. Web. 28 Feb. 2016. <http://0-www.oed.com.catalog.multcolib.org/view/source/a644?result=2&rskey=0Gy7xd&sourceScope=FIRST_IN_ENTRY>.