As a part of our AFAM (African American Studies) 101 course, we were asked to share our thoughts on what we did not know prior to this course. Our group, featuring Kayden L., Aidan P., Carson C., Charlie H., and John M. have come up with 5 podcast episodes discussing our individual thoughts. Nonetheless, we realized a theme in all of our episodes of this mini series. That theme is Perception in relation to Education.

Below you can see how our series, “We didn’t know how education, as well as lack of education builds different perception of African Americans throughout time.” Each episode is also paired with a few resources. We hope you gain some insight into our experiences in AFAM 101.

- Introduction to Podcast Series

- Episode #1: The History of African American Studies and Why it Matters by Kayden L.

- Episode #2: Lynchings in the Psyche of White Society by Aidan P.

- Episode #3: Systematic Racism and its Exclusion from Teachings by Carson C.

- Episode #4: I didn’t know what I didn’t know by Charlie H.

- Episode #5: Africans’ history in Africa and how they were kidnapped and enslaved in Europe and America by John M.

- Conclusion

An Introduction with Charlie, Aidan,

Kayden, and Carson.

Episode #1: Before AFAM 101 I didn’t Know The History of African American Studies and Why it Matters

A podcast by: Kayden L.

**points of clarification: When stating that medical books do not show the difference between diseases in African Americans and white people, it is specific to diseases that show up on the skin. Due to African Americans having darker skin, something like the Chicken Pox would be harder to see and also harder to diagnose if the only reference is images of it on white skin.

Additional information on the topic:

- Bennett, L. (1970). Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America 1619-1964. Rev. ed. Harmondsworth, MD: Penguin Books.

- Stewart, J. B., & Anderson, T. (2015). Introduction to African American studies: Transdisciplinary approaches and implications. Baltimore, MD: Inprint Editions.

- Image citations:

- Davis, B. (2018, February 12). Third World Liberation Front strikes of 1968. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://1960sdaysofrage.wordpress.com/2018/02/12/third-world-liberation-front-strikes-of-1968/

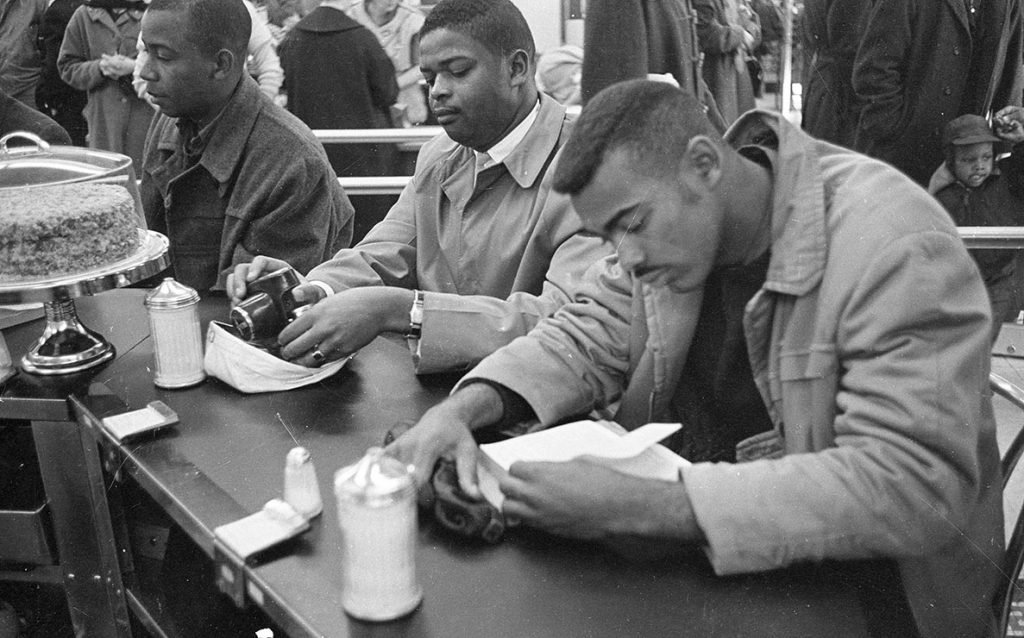

- Wikipedia. Sit-in movement. (2020, August 23). Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sit-in_movement

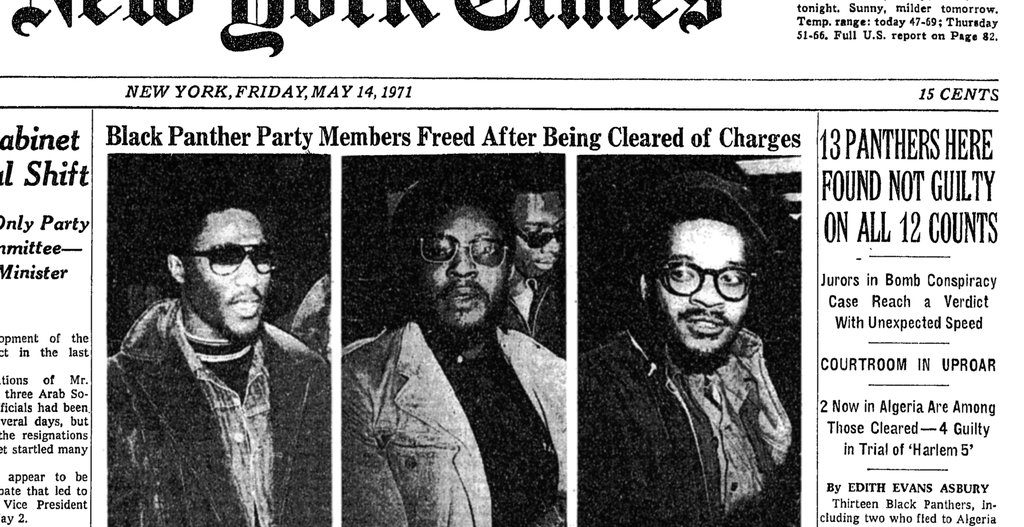

Episode #2: Before AFAM 101 I Didn’t Know That Lynchings Were Accepted By White People

A podcast by Aidan P

**points of clarification: The title of the book is Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America, by Lerone Bennett, not Becket.

Additional information on the topic:

- Bennett, L. (1970). Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America 1619-1964. Rev. ed. Harmondsworth, MD: Penguin Books.

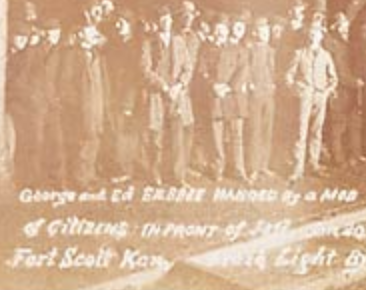

- Allen, J. Littlefield, J. (2000) Without Sanctuary: Photographs of Lynching in Americahttps://www.withoutsanctuary.org/

- Music: www.bensound.com

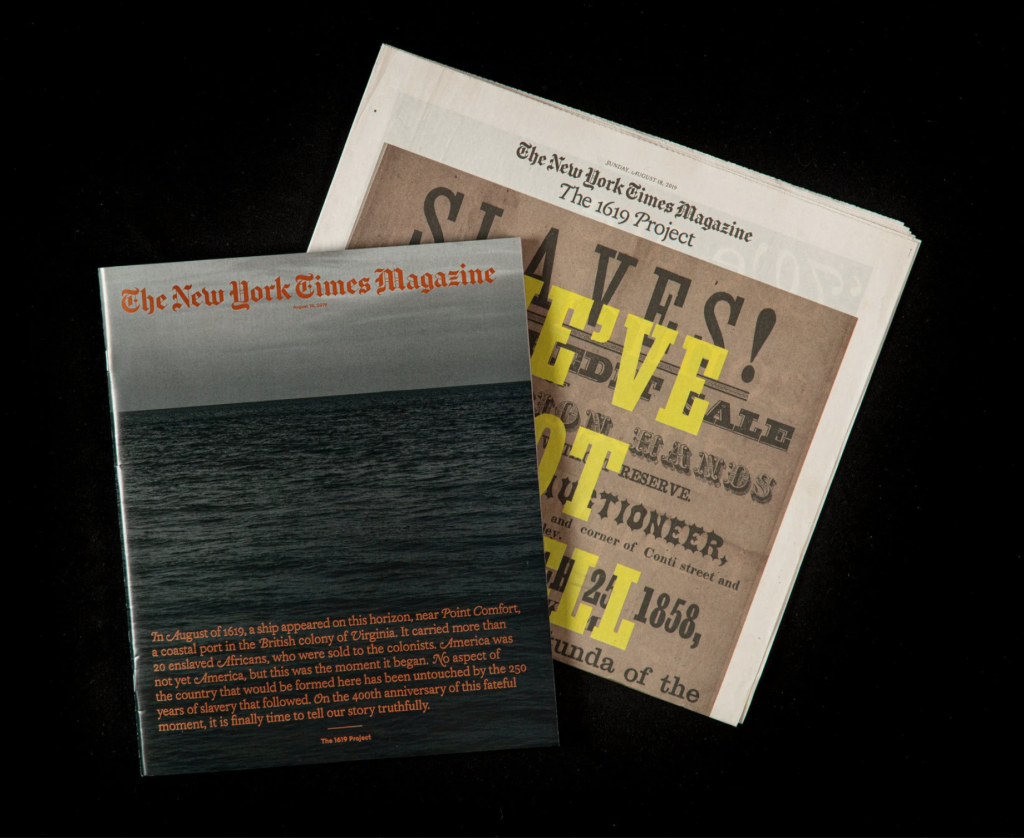

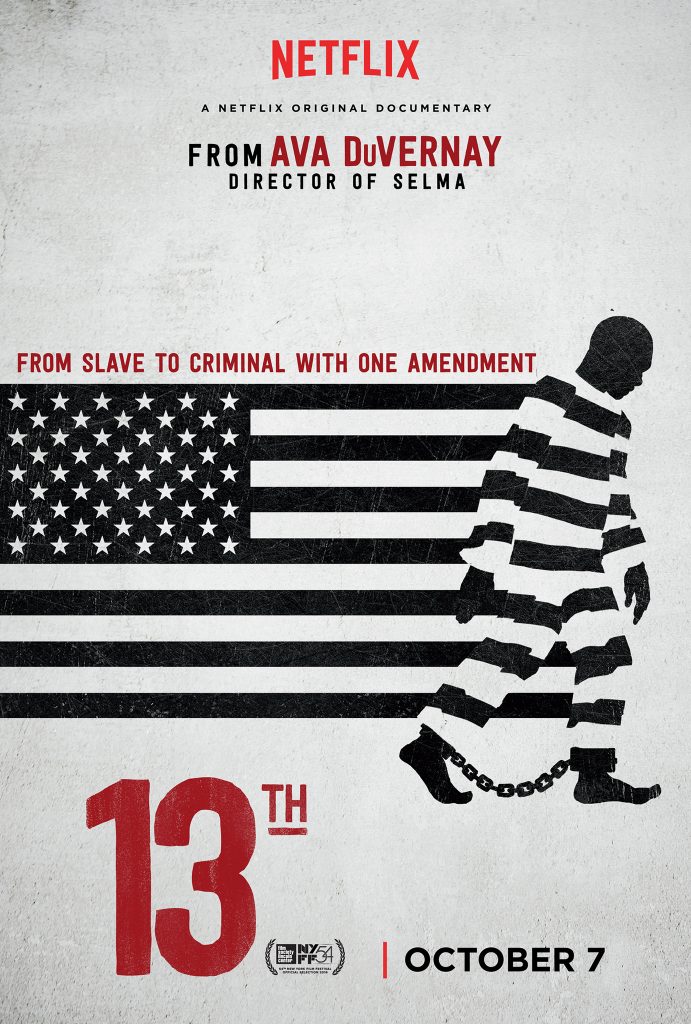

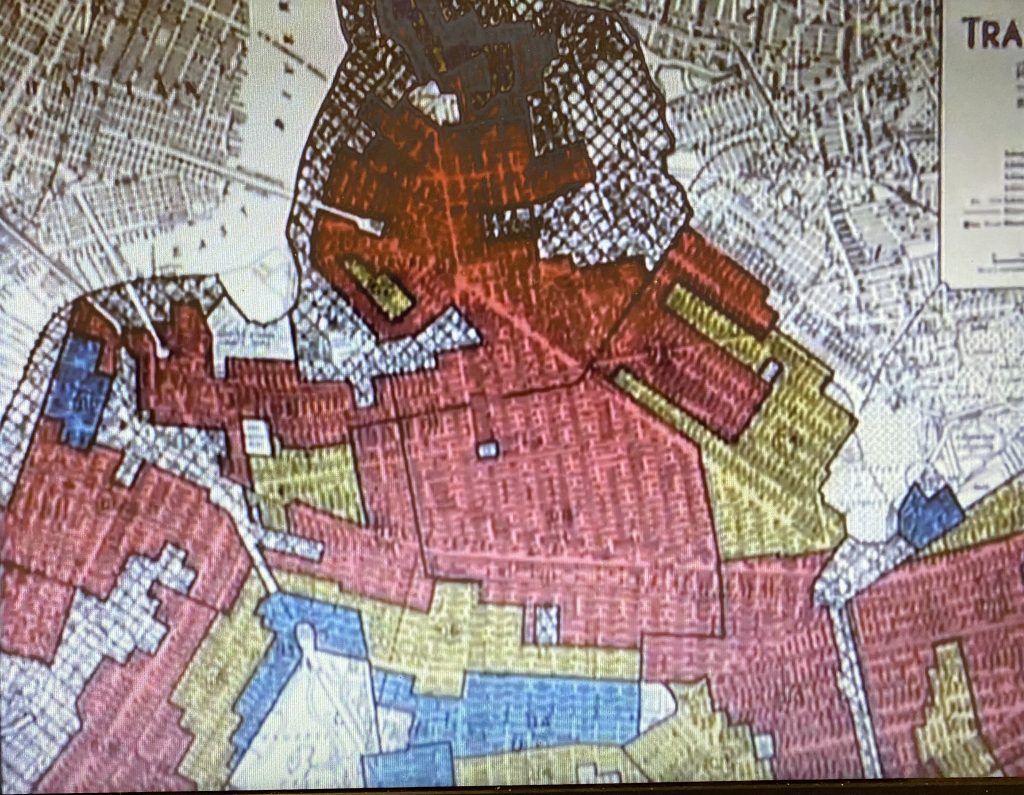

Episode #3 Before AFAM 101 I didn’t know the extent of Systematic Racism and how my Education never Taught me about it

A podcast by Carson C.

Additional information on the topic:

- Gilmer, M. (2015, December 17). Chicago’s deep history of racism gets a brief spotlight. Retrieved October 26, 2020 (image source)

- “The House We Live In: Race—The Power of an Illusion.” Films On Demand, Films Media Group, 2003

Episode #4 Before AFAM 101 I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

A Podcast by Charlie H.

Additional information on the topic:

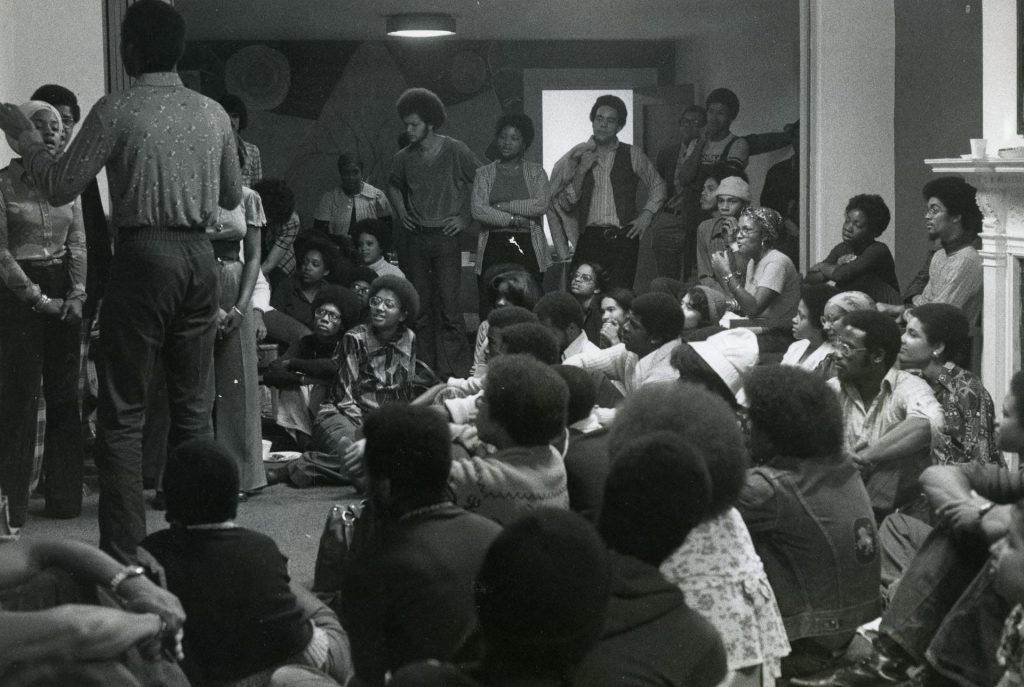

- Image Citation: Maeyama, Jocelyn. A Brief Representative History of African American Studies at Wesleyan, 2019, magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2019/05/20/a-brief-representative-history-of-african-american-studies-at-wesleyan/.

- Citations: Bennett, L. (1970). Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America 1619-1964. Rev. ed. Harmondsworth, MD: Penguin Books.

- Stewart, J. B., & Anderson, T. (2015). Introduction to African American studies: Transdisciplinary approaches and implications. Baltimore, MD: Inprint Editions.

Episode #5 Before AFAM 101 I Didn’t Know Africans’ history in Africa and how they were kidnapped and enslaved in Europe and America

A podcast by John M.

**points of clarification: Due to reading directly from the text Before the Mayflower, the outdated term, “Negro” is used because it is a part of the direct quotes. Please understand that this term is not to be used contemporarily to refer to African Americans, but historically the term was used. Thus the author of the book, Lerone Bennett, an African American historian utilized it as the correct terminology of his time.

Additional information on the topic:

- Bennett, Lerone. Before the Mayflower: a History of the Negro in America, 1619-1962. BN Publishing, 2018.

- Public Library, Chicago. The Americas Before the Mayflower. Hispaniola , 28 Oct. 2014.

Conclusion:

That initial awareness expanded in my first college course in Gender and Queer Studies, which introduced me to a video of Sylvia Rivera, a speech in which she condemned the hypocrisy of gay people who did not advocate for trans people. She spoke to my own feelings of anger toward cisgender gay friends, who perpetuated transphobia and then excused their behavior with “but I’m gay.” Listening to Rivera made me realize how deeply those excuses hurt. Watching the video felt like inheriting a legacy of radical love, which extended from Rivera to me to those in my trans community. I felt connected to her because of our similarities. I celebrated her bravery.

At the same time, seeing Rivera in this video made me aware of how much we were different. I was white and upper middle-class. Acknowledging this privilege helped me see her as she was– a Latinx trans woman who had experienced homelessness, and whose intersecting gender, sexuality and race has shaped her vulnerabilities. I began to understand that Sylvia Rivera and Marsha Johnson were courageous because of ways they differed from me. Their activism was not for me, even though I have benefited greatly from their work. Their activism was for and with those standing at the same crossroads of racial, sexual, and gender oppression.

My whiteness has protected me from ever experiencing racism. When the police were targeting Stonewall, they were targeting LGBTQ+ people of color, people with low incomes, and sex workers. The story about Stonewall that I learned at Pride did not teach me about its connections to the Civil Rights movement and the struggle for Black freedom. I realized that the inheritance of radical love is also a debt: Black LGBTQ+ people are why I have been able to change my name, to go on testosterone, to be true to myself. By virtue of my whiteness, queerness is something I can hide. Being Black, on the other hand, does not have an invisibility option. Pride is about envisioning the future and striving for change. It is about being visible.

At Pride marches, I am reminded that community action cannot happen without individual action. This year, I take Pride as a reminder to dig deep into my discomfort. To ask myself: Are you showing up for the community or are you celebrating your white individualism?

This year, we are participating in Black Lives Matter protests as we also celebrate Pride. We should see them in continuity, as the same movement. As a white trans person, it is up to me to let go of my ego and transform my privilege by listening to black leaders and educators. It is because of my white privilege that I can take up this space with my words. At the same time, merely recognizing my privilege is not enough to make tangible change.

That initial awareness expanded in my first college course in Gender and Queer Studies, which introduced me to a video of Sylvia Rivera, a speech in which she condemned the hypocrisy of gay people who did not advocate for trans people. She spoke to my own feelings of anger toward cisgender gay friends, who perpetuated transphobia and then excused their behavior with “but I’m gay.” Listening to Rivera made me realize how deeply those excuses hurt. Watching the video felt like inheriting a legacy of radical love, which extended from Rivera to me to those in my trans community. I felt connected to her because of our similarities. I celebrated her bravery.

At the same time, seeing Rivera in this video made me aware of how much we were different. I was white and upper middle-class. Acknowledging this privilege helped me see her as she was– a Latinx trans woman who had experienced homelessness, and whose intersecting gender, sexuality and race has shaped her vulnerabilities. I began to understand that Sylvia Rivera and Marsha Johnson were courageous because of ways they differed from me. Their activism was not for me, even though I have benefited greatly from their work. Their activism was for and with those standing at the same crossroads of racial, sexual, and gender oppression.

My whiteness has protected me from ever experiencing racism. When the police were targeting Stonewall, they were targeting LGBTQ+ people of color, people with low incomes, and sex workers. The story about Stonewall that I learned at Pride did not teach me about its connections to the Civil Rights movement and the struggle for Black freedom. I realized that the inheritance of radical love is also a debt: Black LGBTQ+ people are why I have been able to change my name, to go on testosterone, to be true to myself. By virtue of my whiteness, queerness is something I can hide. Being Black, on the other hand, does not have an invisibility option. Pride is about envisioning the future and striving for change. It is about being visible.

At Pride marches, I am reminded that community action cannot happen without individual action. This year, I take Pride as a reminder to dig deep into my discomfort. To ask myself: Are you showing up for the community or are you celebrating your white individualism?

This year, we are participating in Black Lives Matter protests as we also celebrate Pride. We should see them in continuity, as the same movement. As a white trans person, it is up to me to let go of my ego and transform my privilege by listening to black leaders and educators. It is because of my white privilege that I can take up this space with my words. At the same time, merely recognizing my privilege is not enough to make tangible change.

Here is my challenge to myself, and to you, fellow white LGBT people:

Here is my challenge to myself, and to you, fellow white LGBT people: