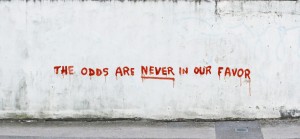

In which the odds are never in our favor.

To my dear reader,

If there is one rule of writing that has stuck with me from my high school creative writing class, it is “Show, don’t tell.” If there is one memorable piece of literature that broke this rule, it is Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games Trilogy.

The rule “Show, don’t tell” is a way to elicit sophisticated description from writers, ensuring a more tangible world for the reader. If a character is mean, for example, describing them as “mean” sounds juvenile and imprecise. Instead, the writer should show the character making snide remarks about their younger cousin’s only bedraggled doll or framing their mother for second-degree murder. Have the character demonstrate their qualities, and let the reader decide what those qualities are.

Collin’s trilogy broke this rule countless times, much to its detriment. I clearly remember the character Finnick Odair in Catching Fire revealing its infamous President Snow’s murderous past. Rather than actually showing the reader Finnick’s words, however, Collins leaves us with a description of a web of vicious crimes too evil to believe.

Why don’t you tell me what Finnick said, Suzanne, and I’ll decide what’s too evil to believe?

And yet for all its faults, I commend the trilogy for its premise and themes, and more importantly, I commend the film adaptations as elegant, efficient narratives that clarified the relevant themes of the (all too often convoluted) books. With Collin’s heavy-handed, poorly paced narration out of the way, the contrast of extreme poverty in Panem’s districts against the lurid consumerism of Panem’s capital, as well as the trauma of violence on children, came into sharp relief.

It is an incredible shame that the trilogy’s awkward prose, alongside the barrage of other youth-in-dystopia stories, have come between the public and the parallels between Panem and our world. As I write this, Chicago’s government and police department come under ever closer scrutiny in light of the case of Laquan McDonald, twisting ever harder out of systematized responsibility for the seemingly endless police brutality. President Snow would be proud.

But not everyone dismissed the relevance of Collin’s work. At the premiere of the Mockingjay Part 1 film, rumors of the Thailand government banning the film began to circulate. The reason, rumors went, was a scene in which the impoverished masses of one of Panem’ districts ban together in a suicidal mission to destroy the dam that supplies Panem’s capital with power. Fearful that the movie would inspire rebellion, just as Katniss inspired the districts, the Thai government removed the film from theaters.

I am not suggesting that the villain of our story is the government. It is not the president, or every policeman. It is not every white person, or every black person, or everyone that is neither black nor white. It is not Syrian refugees or Muslims or Russians or Chinese. It is the President Snows of the world, who make others’ lives their toys so that they never have to play in the Hunger Games.

Remember who the real enemy is.

With all due respect,

Daniel Wolfert