Boomsday is a book authored by the famous satirist Christopher Buckley (most famous for ‘Thank you for Smoking) about a young blogger who gets fed up with the baby boomer generation’s excessive social security payments. In order to solve this mounting debt crisis, she proposes that the government provide incentives for people to ‘transition’ themselves when they reach the age of 70. This book was published only a few months before the beginning of the recession, and many people at the time were warily eyeing the exponentially increasing costs of social security as a problem down the road. While Social Security is still an issue of great import, there is an entirely different problem (in fact, the exact opposite problem) occurring amongst the baby boomer generation: they just won’t quit working.

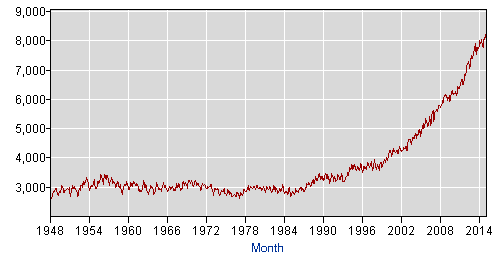

It’s very well known that more and more people are opting to work beyond the typical retirement age of 65, and the proportion of the workforce in this group is growing. The Atlantic published an article just yesterday about this relatively new trend, citing BLS numbers that project a 23 percent participation rate in the over-65 age group by 2022. As it is, the employment for typically-retired individuals has skyrocketed since the mid-eighties.

The argument in the Atlantic’s piece is that this trend comes from two places, the abolishment of mandatory retirement in 1986, and that many jobs these days require skills that get better the longer you practice at them, or what the Atlantic calls ‘age appreciating.’ However, there’s another reason I can identify why older people are opting to keep their jobs beyond typical retirement age, and it has to do with what economists call ‘hedonic wage theory.’

In essence, hedonic wages speak to the fact that people have preferences in regards to where they work (what a breakthrough.) Generally, this theory is applied to the risk of any given job, with some employees more willing to take on risky work-environments than others. It works like this: imagine ‘Coal Inc.’ is a coal mining company and they currently have no safety equipment, no helmets, no headlamps to see where you’re going in the mine and no rescue plans in place. The person who opts to work for this firm is pretty brazen, and also very likely to get injured. The company can offer this employee relatively high wages because they haven’t invested in any of the safety equipment. On the other hand, we have ‘George’s Coal Company’, who are VERY safety driven. In fact, no people go into the mine at all, and piloted drones do all of the mining. There’s almost no chance of getting injured at ‘George’s Coal Company,’ but they can’t offer the same high wages as ‘Coal Inc.’ because they’ve had to pay for all of this safety equipment. The question is, which firm do individuals pick? The answer comes down to, ‘it depends.’ Individuals who are afraid of risk are more likely going to pick the safer firm because they get more personal benefit from their safety than the higher wage of ‘Coal Inc.’ offers them. On the other hand, someone who is less-worried about risk might take the extra pay because that higher wage makes up for the chance that somebody puts a pickaxe through his boot because they can’t see.

So what does this have to do with the higher number of people 65 and older continuing to work? Quite a bit. Many people stereotype older individuals as being typically more risk-averse than younger people, but in fact this choice makes a lot of sense. Workers who are 65 and older are more likely than any other age-group to be fatally injured on the job by a wide margin.

While I can buy that more jobs require skills that are acquired over a longer timespan than they did previously, I also know that the number of workplace injuries in the US has trended downwards for a very long time

With this is mind, a decrease in the riskiness of the workplace overall will, through hedonic wage theory, correlate to an increase in the willingness to work of employees 65 and older because those employees are going to be more likely to value a safe workplace, given that injuries are far more harmful to them than to their younger counterparts. Thus, we should see an increase in the participation rate of individuals in the older age brackets, as work environments get safer and safer.

Of course, this is a big problem for a number of reasons. First, the more people who work later and later in life will necessarily take positions away from younger people who are looking to enter the labor force, depriving them of important workplace training, which is especially important in the post-recession world. The second reason is that, in general, contracts are structured to extract value from the employee at the beginning of its term, and return that value to the individual as the contract reaches its conclusion by building in year-by-year wage changes. If workers continue to work beyond the intended conclusion of the contract at higher and higher rates, contracts will become increasingly unbalanced in the favor of employees. This will force firms to offer less generous raises over time, and make workers who would have otherwise been willing to retire at 65 work beyond that age to achieve the same benefit, further squeezing out younger potential employees.

While ‘Boomsday’s’ predictions have not come to pass, there still is a worrying trend in the world of individuals extending their careers beyond their intended range, made doubly concerning by the fact that these trends are happening world-wide.